4 Big Challenges for Project and Engineering Leaders to Solve

In most parts of the world, these are difficult times for the capital projects community. Hence, it is extremely challenging to run a projects and engineering (P&E) organization[1] in an industrial company today.

The returns on project opportunities are thin no matter what business lines our corporations want to grow (e.g., renewables, refining, oil and gas, some areas of mining, chemicals in general, and some specialty chemicals). The inflationary environment over the last few years, coupled with muted worldwide economic growth, has squeezed industrial firms from both sides, stagnating demand[2] and increasing the cost to build and run projects. If the IRR or NPV per project was the only concern, our path would be more straightforward. However, there are a lot of external factors raising the business case risk—legislation, permitting, tariffs and trade wars, local content, increasing cost of capital, lack of certainty around subsidies, and so on. The endless list means most projects today include multiple potential showstoppers.

These unusually uncertain risk configurations make business leaders anxious. This, in turn, makes the journey for the P&E organization to deliver an asset (or a project) for the business from start to finish quite challenging; it also makes the portfolios of projects in our industrial companies very difficult to execute. These risky configurations are the foundations upon which projects need to be done.

I would like to talk through the 4 biggest challenges for project and engineering leaders to solve:

- Project organizations are slow in the front-end

- Execution today is just a mess

- Projects are too expensive to get going

- Project governance is eroding

These issues come directly from data and studies IPA has been doing over the last several years, along with multiple conversations with the companies at the P&E leadership level. The goal is not to scare and shock, but to explain some of the root causes behind these challenges, so we can begin to tackle them as a projects community. Although some of these problems appear overwhelming, every P&E executive I have spoken with is excited to meet the challenges that lie ahead.

1) Project Organizations Are Slow in the Front-End

The biggest internal headache today is the delivery of owner companies’ work. The most frequent complaint against projects is that the deliverables produced for the gate reviews are poor quality and routinely late, with too much time needed to complete the front-end work. IPA’s data back this claim: P&E organizations are slow[3] in the front-end and the quality of the deliverables at the gates is degrading.

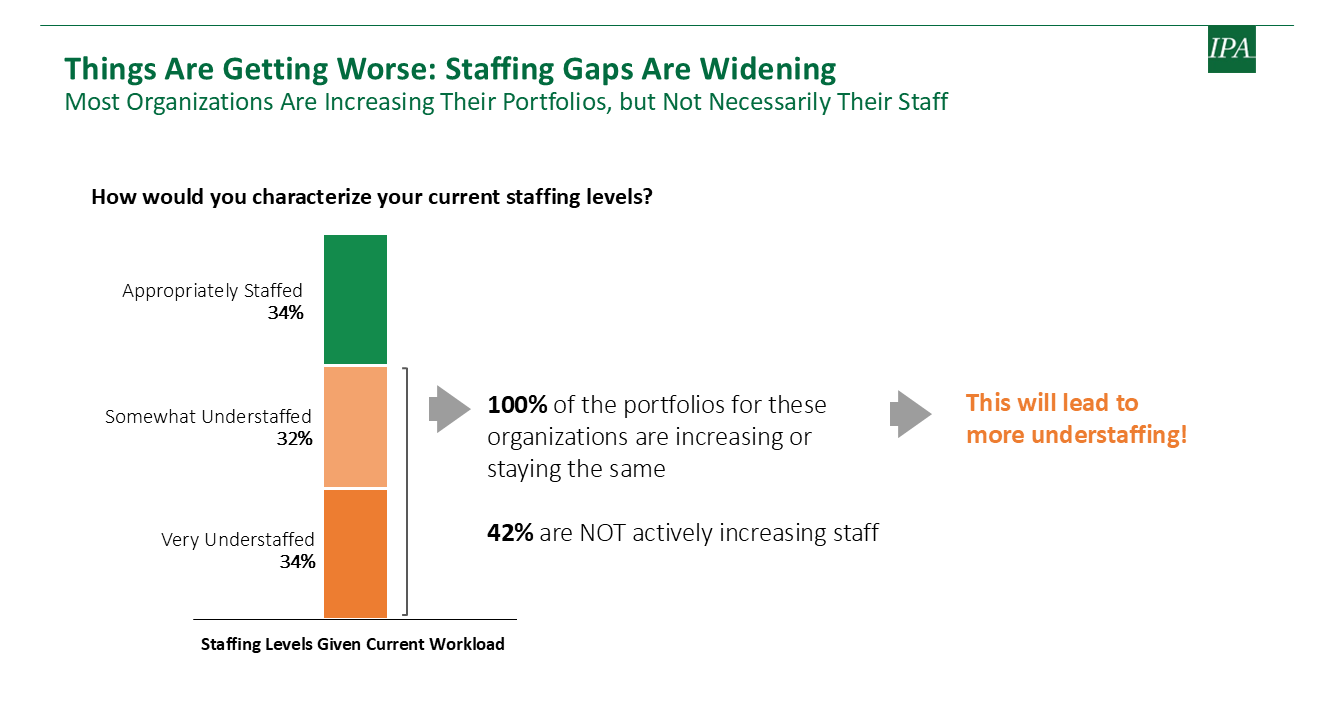

The root cause of this is people—we don’t have enough people, we don’t have the right competencies, we don’t have the needed experience, and we don’t have a middle to train the people we recruit. In our conversations with the owners of 25 industrial firms in a study done in 2024, two-thirds consider themselves to be understaffed—even anemic—and they are being asked to do more with less (see Figure 1).

Looking back, no single event triggered this situation. Owners faced a demographic issue prior to the pandemic and COVID only accelerated the issue. Further, the portfolio explosions after the pandemic that forced companies to transition quickly back to pre-COVID staffing levels left projects organizations with even more people problems.

For P&E executives today, it is essential to answer four basic questions about their projects organization:

- What does our long-term portfolio look like?

- How many people do we need for this portfolio?

- How many people do we have today?

- How do we close the gap?

When we can honestly answer these questions around resource planning, we can determine the right size either on the portfolio side or people side. However, as long as these two sides remain unsynchronized, we will continue to be slow in the front-end.

2) Project Execution Today Is a Mess

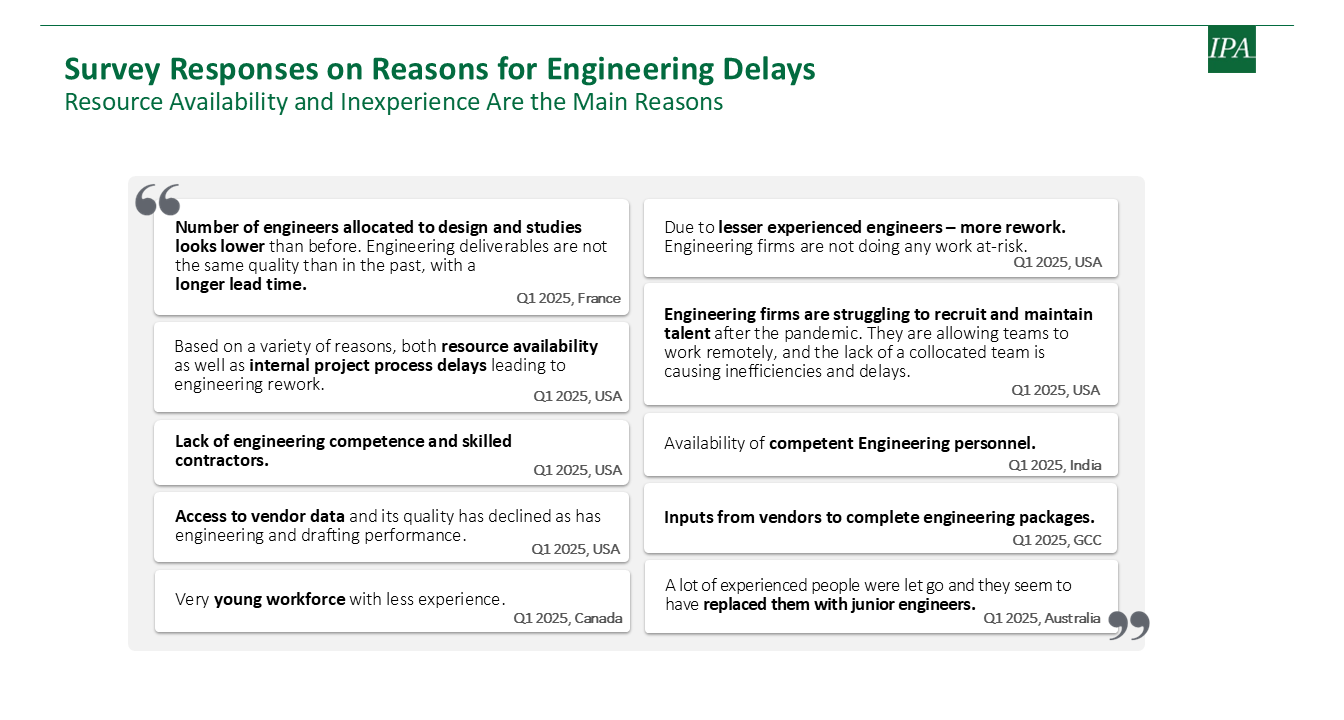

The same demographic challenges that owner companies face—multiple senior-level and entry-level personnel and not enough in the middle to train and manage staff—are affecting engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contractors. The EPC contractor demographic situation is only worsening as owners continue to steal and borrow personnel (e.g., IPMT[4] model) and contractors steal from each other. Our latest market trends survey[5] backs the hypothesis that the lack of resource availability and inexperience in the EPCs are the main reasons for the delays (see Figure 2).

The common complaints that owners have against contractors in execution is that the EPCs don’t meet their field productivity or engineering delivery commitments. These complaints are valid. Engineering on engineering-intensive projects is now routinely late, and history shows that when engineering is late and out of sequence, it has major effects in the field. Our IBC 2025 database shows that engineering slip on onshore industrial projects averages about 50 percent and a routine onshore project is delivered 3 to 6 months late on average. That is shockingly weak performance.

This engineering slip is probably the most urgent problem that our community needs to address. We are getting more calls from clients to perform mid-execution cost and schedule risk analyses (CSRAs) of projects in execution. IPA is ready to step in and help no matter what stage a project is in, but unfortunately it is very difficult for owners to reverse the situation when the project goes off the rails in execution (though re-baselining and other actions can help prevent it from becoming worse). Any interventions will be hard and can be damaging. For P&E leadership, the focus in the short term must be to ensure that engineering is correct and slips as little as possible. There are ways to fix this: we need to beef up the number of engineers we are assigning to projects to monitor design progress and complete quality control (QC). If we don’t reverse this trend in weak engineering, the typical large complex engineering project in execution today will inevitably last much longer than planned.

3) Projects Are Too Expensive to Get Going

What we hear from those executives whose portfolios include multiple projects in the front-end that haven’t entered execution is this: “Projects are just too expensive to get going.”

We know EPCs struggle to deliver on engineering quality and productivity in the field, but there is another area where things are out of control—supply chains and vendor delivery times.

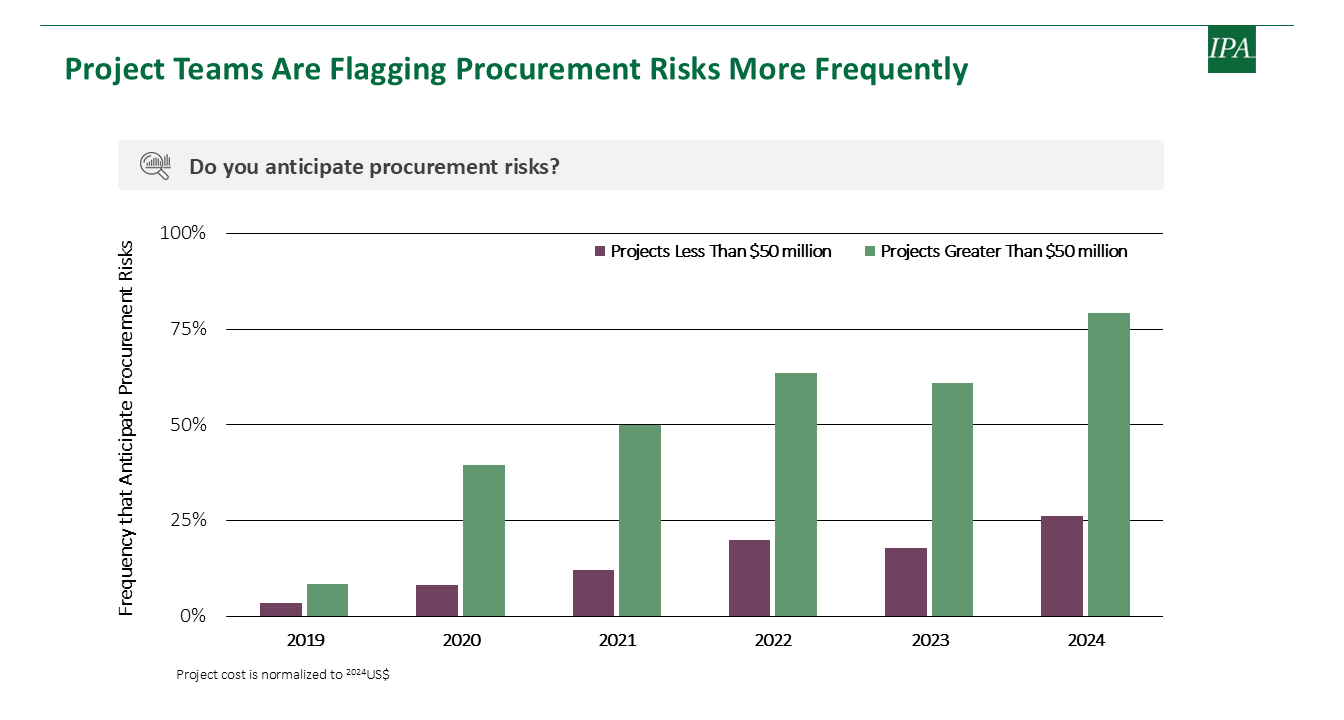

We keep close tabs on how the supply chain is affecting capital projects by analyzing a combination of IPA project evaluation data and public data, as well through our Market Trends Survey, and both measures tell the same story. Supply chain issues continue to persist as they have still not snapped back post-COVID, and these issues continue to be the primary driver of risk on projects. Over 75 percent of the projects IPA looked at costing over US$50 million in 2024 flagged procurement as the major risk on their projects, and this number has steadily climbed since 2020 (see Figure 3).

Anecdotally, equipment with an 18-month lead time pre-COVID now takes 24 months to deliver. We hear that suppliers are stretched and not investing in capacity expansions. It is becoming increasingly clear that it is time to accept that supply chains will not snap back: Do not expect a return to a shorter lead times anytime soon.

The problems in execution, coupled with the problems in the supply chain, mean that these EPC contractors have become extremely risk averse.

Driven by the problems contractors are facing today, including their own struggles, they seek to avoid lump-sum contracts, even though the construction/fabrication market is not overheated and commodities prices are not high or rapidly increasing.

P&E executives then are stuck with thinning bid lists, fewer bidders, extreme push back on terms and conditions, and long negotiations, and any risk they try to transfer is priced in with higher premiums. We live in a world of sticker shock: When the bids come in at FID, we have the “OMG at FID” phenomenon as we realize that our projects are not affordable and we can’t get them off the ground.

Given today’s contracting environment and fear of risk, IPA’s contracting experts have been helping our clients design their contracting strategies for projects in FEL 2 by bringing historic data to bear on the current context. For P&E executives, we have strongly been advocating that owner firms take a deep dive into their terms and conditions, looking closely at risk transfer, liability terms, and liquidated damages to find ways to make projects less risky for the contractors and hence more affordable. We also are also actively helping companies via deep benchmarking in the early phases to help them get the scope cost right the first time around.

4) Project Governance Is Eroding

In large, complex projects, especially those tagged as strategic, schedules are frequently based on working backward from an end date. This means that at some point, projects need to start execution no matter how well or poorly defined they are on the front-end. The supply chain issues that are elongating delivery times also mean many more long-lead items need to be ordered prior to the final investment decision (FID), so more and more projects are committing a larger percentage of their total CAPEX prior to FID.

All of these issues are a problem, as discipline in the front-end seems to be eroding. We are seeing that investment decision gates no longer hold the same authority and, as project governance erodes, projects are being pushed through into execution with weaker definition.

P&E executives need to be able to communicate clearly with their leadership that these are very difficult times. Driving project schedules from start to finish without good foundational owner-controlled practices will ultimately result in execution nightmares and shareholder wealth destruction.

In certain companies, that message can’t be delivered because of the way P&E is organized—they essentially see the business as their client versus their partner. If you find yourself in one of these companies, it is important that the P&E organization elevates itself to have a seat at the executive table. If P&E executives do not sit at the leadership table, they won’t be able to solve the deep problems facing today’s projects organizations.

What’s Next?

Although we know that these are difficult times for the projects community, it is essential that we don’t get discouraged. Rough patches are nothing new to our industrial sectors—we haven’t exactly been here before, but we have gone through similar periods. We need to lay out long-term plans and keep working hard to meet these challenges, including helping the contractors. We need to keep educating the businesses around the reality of today’s markets and how projects work. If you are a P&E leader or executive, be excited by the challenges that lie ahead of you. Big problems are always fun to solve!

[1] These leaders in industrial companies are responsible for overseeing and guiding the entire engineering and projects organization within a company and sometimes this includes the Technology and R&D area.

[2] The recent OECD interim report (March 2025) revised global growth downward for both 2025 and 2026.

[3] Data from recent projects in IPA’s database indicate that the time to take a project from the start of the scoping phase (FEL 2) to final investment decision (end of FEL 3) has increased by 15 percent since the pandemic for projects of the same complexity.

[4] An integrated project management team (IPMT) brings together functions with different areas of expertise to deliver complex projects.

[5] Since the pandemic, IPA routinely surveys owner organizations on the state of the EPC market, including the supply chains. We routinely gather survey responses from over 35 industrial companies across the globe in all industrial sectors working in major capital projects.