Defending the Front-End Loading (FEL) 1 Gate

In a recent study for IPA clients,1 we asked people how frequently these statements about the opportunity assessment phase of the capital project development process, referred to as front-end loading (FEL) 1 by most companies, were accurate:

- The projects in FEL 1 address a true business need

- The alternatives for meeting business goals were explored thoroughly

- The economic analysis used to evaluate potential benefits was robust

The most common response was “sometimes,” meaning that for some projects the FEL 1 work was done thoroughly, but for others it was done haphazardly. This feedback is a true reflection of a pervasive problem for approximately 8 of 10 capital-intensive companies. That is, there is wide variability in the rigor and discipline applied to projects in the FEL 1 phase.

This inconsistency has serious consequences. Some projects will have weak business justification. Others will move too quickly thorough alternative selection. Still others will have cost and schedule estimates containing much more risk than anticipated. Ultimately, inconsistent FEL 1 leads to portfolio management mistakes, higher sunk costs, and excessive capital project spending, all of which reduce shareholder wealth. Consider the ways inconsistent FEL 1 work undermines portfolio management, which depends on evaluating competing capital investment opportunities on a level playing field. Projects that have not done a thorough market analysis may overstate expected revenue. Projects that have slapped together a capital cost estimate have probably underestimated the eventual investment required. These projects will appear more attractive than the projects whose cash flow estimates are rooted in more realistic assessments.

⇒ SUBSCRIBE TO IPA NEWS & INSIGHTS

Sources of the Problem

Inconsistent FEL 1 has many sources. Time is often a culprit. Time pressure to meet a market window or to gain access to resources often leads to shortcuts in the first phase. For some of these companies, the problem can be traced back to poor integration between the business planning process and project development process. The business strategy process fails to move projects into the project development process early enough to allow for high-quality work to be performed by functional specialists on the project team.

For many companies, the lack of qualified project sponsors is also problematic. The project sponsor, the person delegated by a business to lead the development of the initial business case, has a crucial role. The project sponsor must guide the definition of business objectives, provide input on preferred alternatives, gain stakeholder alignment, and reconcile competing objectives, all of which are necessary for a reliable business case. Despite its importance, only 60 percent of IPA clients have formally documented the roles and responsibilities for their project sponsors.

While fixing process deficiencies or plugging resource gaps is necessary for improvement, in the end, the only way a company can ensure consistent, high-quality FEL 1 is with a strong gate at the end of the opportunity assessment phase that is capable of stopping projects that are not in compliance with company requirements for moving into the scope development phase of project development, or FEL 2.

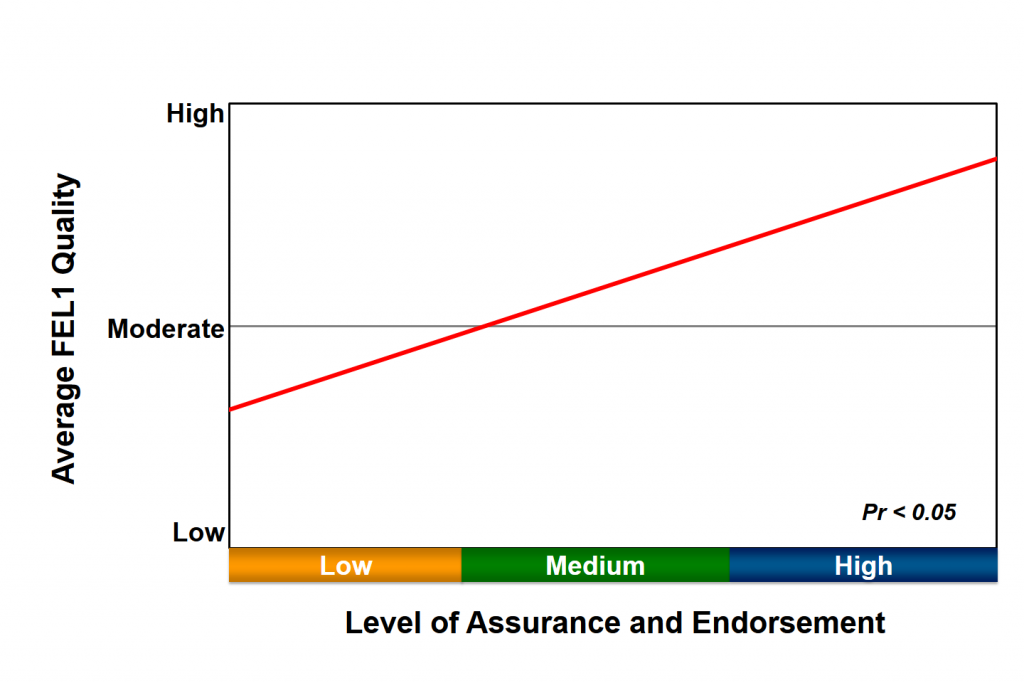

Of course, it would be better if people always did the right thing and followed company guidelines, but for a variety of reasons they do not and will not if there is no mechanism to force compliance. In other words, what gets asked about tends to get done. Figure 1 (right) shows the relationship between the average FEL quality of a company’s project development process and the level of assurance and endorsement that the company performs on key FEL 1 deliverables. Only companies that have a high level of assurance and endorsement have consistently high-quality FEL 1.

The Weakest Gate

Forcing “compliance with requirements” smacks of rigidness and bureaucracy. But it is important to remember that the FEL 1 process is really just a structured, logical approach to answer a series of questions:

- What is the business opportunity?

- What the best way to take advantage of this opportunity?

- Does the potential benefit from this project justify further work?

- Is this project a higher priority than other opportunities competing for scarce resources?

The process is meant to foster creativity and to improve decision making through better definition of objectives, constraints, and potential options. At the end of FEL 1, there are still many unanswered questions about the exact shape of the project. Different scope options are being considered and the capital cost estimate still has a wide-range of uncertainty, +/-50 percent for some companies. A strong FEL 1 phase increases—rather than reduces—the chances a project will be a business success.

Implementing assurance and endorsement at the FEL 1 gate is generally harder than at the FEL 2 and FEL 3 gates. Although those phases are typically led by the projects organization, the FEL 1 phase is almost always in the business’ domain. Businesses are tasked by corporations to find promising investment opportunities. The FEL 1 phase is when businesses identify, screen, and prioritize which capital projects will be pursued and which will be deferred. The resources needed to develop the initial business case also usually reside within the business unit. It is logical that the businesses run FEL 1, but there must be corporate oversight of the gate. It is almost impossible for a business unit within a corporation to effectively police the FEL 1 gate by itself. There are simply too many forces that undermine the discipline.

Reinforcing the Gate

Companies can effectively implement corporate oversight through two functions: (1) the corporate finance department which either builds or reviews the project’s economic model and (2) the central estimating function that either develops or reviews the FEL 1 conceptual estimate. For petroleum and mineral companies, a corporate group is tasked with reviewing and endorsing the resource estimation. These mechanisms should be suffi cient to identify gaps in the FEL 1 deliverables.2

Stage-gate assurance and endorsement alone is of course not a fail-safe system. The gatekeeping process must also include the appropriate checks and balances so that the information from the reviews is actually used in the stage-gate decision. For some companies, the lack of endorsement from a functional leader is in effect veto authority and stops the project from advancing. More commonly, a cross-functional governance board will take the input from the reviews and judge whether the project is ready to proceed. This method is an effective way to stimulate debate and to garner support among key stakeholders provided the board members have similar levels of seniority. Governance boards can easily become rubber-stamp committees if one person has the authority to downplay or dismiss the concerns of the other members and push a project forward.

Strengthening the gate also provides the benefit of forcing improvement back through system as people realize it is easier to complete the work right the first time. Ideally the system will reach a balance where only occasionally projects must be stopped at the gate. Companies, however, must remain vigilant and monitor the functioning of the FEL 1 stage gate. The balance that produces suffi cient rigor and discipline for effective decision making while avoiding wasteful bureaucracy is easily upset. There is a tendency in Industry to add layers to the review process in response to unique situations in which a project should have been stopped, but was not. Eventually the reaction to excessive reviews is to cut them back so much that the gate no longer functions properly.

Like anything that is important to a company, the operation of the process development stage gates, including FEL 1, must be carefully managed to ensure its effective operation. Although there is probably little appetite for adding another management task, a strong FEL 1 gate pays significant dividends to shareholders.

How IPA Measured Assurance and Endorsement

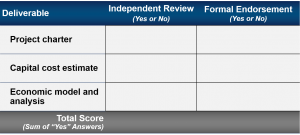

Our measure of the level of assurance and endorsement was generated by adding up the types of reviews each company that participated in our study performed on three main elements of the initial business case:

- The project charter

- The capital cost estimate

- The economic model

The intent of assurance and endorsement is to verify that the information underlying the FEL 1 stage-gate decision is reliable. We distinguished between assurance and endorsement. Assurance is an independent review of the underlying work that is passed to a gatekeeper or decision review board as input to the stage-gate decision. Endorsement in the attestation by a functional manager that the work was done properly and that they take accountability for the quality of the work.

Total scores were combined into an index to measure the overall level of assurance and endorsement.

1 Paul Barshop and Annalynn Jacob, FEL 1: Setting the Foundation for Doing the Right Project, IBC 2014, IPA, March 2014

2 Megaprojects or other company-changing projects likely require a broader set of reviews to ensure contextual issues are understood and that there is suffi ient stakeholder support for the investment.