Early Uncertainty in Sustainability-Driven Projects

An unusually large percentage of the sustainability-driven projects that IPA assessed early in their lifecycles—before the scope is set—experienced extensive churn in their later phases, often not making it to full funds authorization. Many of these projects failed to properly recognize and address the early uncertainty and increased risks that sustainability-driven projects face in their lifecycles. Developing a clear business case, with an understanding of risks and uncertainties and their root causes, is critical to assess whether the project has a chance to maintain business value during its development in later phases. Although important for all projects, this is especially critical for sustainability-driven projects, which often have marginal business cases. Recognizing these risks and uncertainties early is also critical to establishing kill criteria and mitigation plans that often require venture shaping that is outside of the project team’s typical work.

Early Definition Uncertainty

The end of FEL 1 is a uniquely critical milestone for carbon removal, new energy, and circularity projects. The financial expected return of most of these projects just meets investment hurdle rates, even with government subsidies. Thus, any meaningful growth in estimated operating or capital costs or significant delays can make these projects uneconomical. These business cases also have a wider range of uncertainty than most ventures at the end of FEL 1.

All projects face some risk of uncertainty at the start of FEL 1, the project initiation phase. However, projects in emerging industries face increased risk because of their characteristics, including early definition uncertainty from:

Immature pricing markets and commercial models: Some products—such as sequestered carbon, blue or green ammonia, and blue or green hydrogen—lack an established market and thus lack an established price. This makes determining a project’s viability difficult and much more dependent on business and venture development focused on customer and price certainty development.

Untested requirements for government subsidies: Government subsidies are often required to make sustainability-driven projects financially viable. These government subsidies, however, are often unclear and come with strings attached. Marginal projects need long-term certainty in product price and need enough time on the front end to properly develop. Schedule pressure to qualify for financial support often does not leave project teams with enough time to develop and deliver a project with a business model that is fundamentally focused on low cost.

Evolving and lengthy regulatory and permitting processes: Many sustainability-driven projects enter uncharted regulatory and permitting territories, where existing laws might be unclear, rules are undeveloped, and regulatory agencies are inexperienced. In addition, the regulatory framework can also be local and therefore variable across regions. One recent example is the Navigator CO2 Pipeline Project, which was put on hold after South Dakota regulators denied a crucial permit. Another is a blue ammonia project planned for Mississippi, which ran into problems with uncertain permitting requirements. Failing to receive the required permits is truly a showstopper for these projects and is often hard to predict, even if the company is working closely with regulators.

Fragile engineering services and equipment supply chains: Not only do project teams need to find vendors who can meet their needs at a cost they can afford, but they also need to be concerned about whether those vendors will still be in business when upgrades or refurbishment is needed. Further, with a limited number of service and equipment suppliers, companies are competing with each other to lock in agreements to ensure their availability. Balancing locking in agreements—when prices are still high—with waiting for the market to come down is a balancing act. Lastly, the sheer scale of many energy related sustainability projects is such that vendors, particularly of components with high intellectual property value, are often unable to scale up in a timely manner to provide the necessary supply of their product.

Low technology readiness level: Sustainability projects often require deployment of new technology. Commercializing these new technology projects presents a high risk of significant cost overruns, schedule slip, production shortfalls, or outright failure. These projects take longer to start up, require more contingency, and often take longer to reach steady operation than projects using proven technologies. A robust technology management plan is needed to ensure Basic Data are ready as process design starts and to prevent projects from moving forward with untested technology. Basic Data development often takes time, which collides with subsidy and business requirements.

Ensuring Only Viable Projects Move Forward

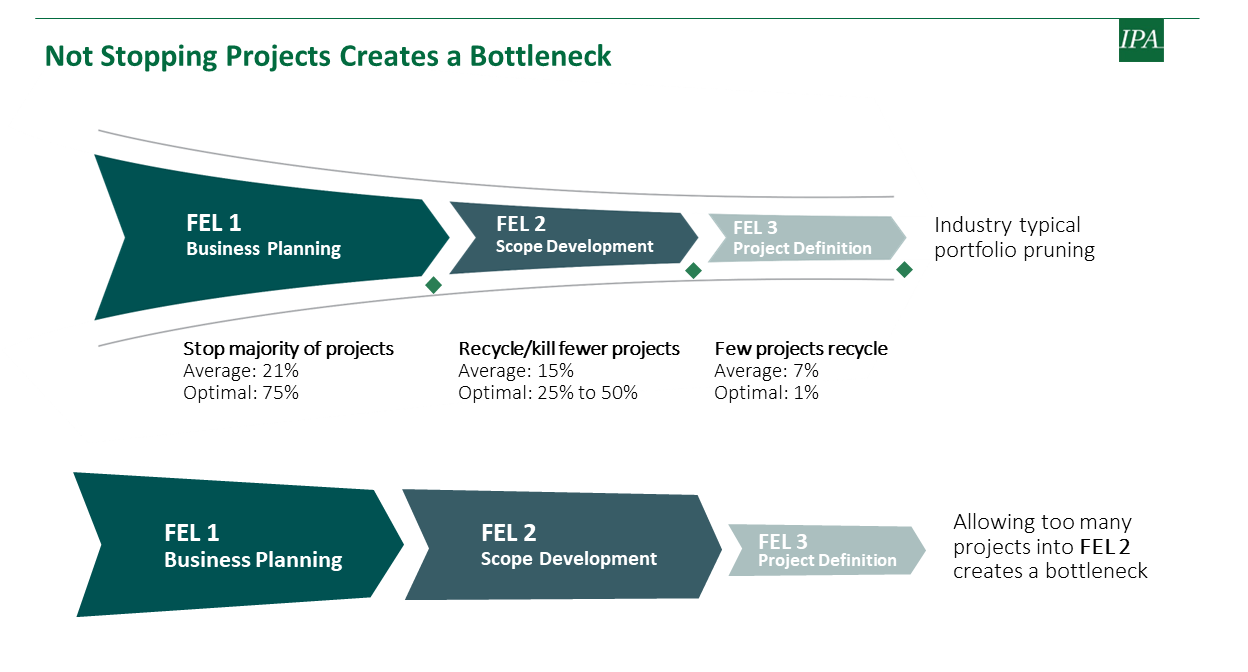

Completing FEL 1 without a business case underpinned by robust analysis and detailed shaping and risk management strategies leads to significant churn and delays if the project enters later project development phases. These projects either do not progress out of FEL 1 or proceed to FEL 2 (and in some cases even FEL 3) only to languish and eventually be canceled, creating bottlenecks in the project pipeline (see Figure 1). Failure to complete FEL 1 business planning activities also leads to large sunk costs and wastes internal resources that could have been used to develop ventures with a higher probability of success. Thus, assessing a project’s viability early is critical to developing and maintaining a successful project portfolio.

How IPA Guides Companies Through Early Uncertainty

As sustainability is now an important part of decision-making for industrial capital projects, it is critical for companies to properly address uncertainty in the early definition stages. IPA brings decades of experience and a wealth of data-based knowledge to help companies make informed early decisions to drive success and avoid pursuing unprofitable ventures.

The business case is the single most important element in building an effective capital project. IPA research has shown that the quality, depth, and completeness of the business case governs virtually every aspect of project development and execution. A Project Viability Assessment (PVA) helps you understand the strength of your project’s business case, identifies gaps in practices, and highlights actions to minimize project risk in the remaining phases.

For new technology commercialization projects, it is imperative to understand how likely the project is to meet its cost and schedule targets, as well as the potential risks and how to reduce them. IPA can provide an unbiased picture of a project’s cost, early operational performance, and schedule through a New Technology Risk Analysis. This gives management the information and confidence needed to make informed early decisions.

To meet the needs of startup companies and less experienced project systems, IPA offers a comprehensive end-to-end advisory solution—the Project Delivery Guide (PDG)—to steer companies through all the critical tasks from FEL 0 through project execution.

These are just some examples of IPA’s capabilities in addressing early uncertainty in capital projects. Complete the form below to request more information.