How Capital Project Teams Can Do More With Less (Without Failing Miserably)

If there is one thing owner companies agree on, it is that they do not have the people they need to effectively execute the work they want to do. In fact, 73 percent of capital project teams are missing critical functions, using inexperienced people in leadership positions, or generally understaffed. Although this is not a new problem, it will not be going away anytime soon, and simple demographics suggest it is likely to get worse in the near-term. Worldwide, 9 percent of the population was 60 years old or older in 1990. In 2013, that number had risen to 12 percent, and in 2050, it is projected to be 21 percent. More and more experienced talent is leaving the workforce through retirement and semi-retirement, and there is not a sufficient pipeline of talent, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) disciplines, 3 to adequately fill the gap. As a result, owners have to rely more and more on contractors to execute their portfolio of projects or simply try to do more with less. When compared to project teams that are adequately staffed by owners, these approaches achieve degraded project performance to the tune of 25 percent worse cost competitiveness, 22 percent higher cost growth, and 5 percent worse schedule slip. Given the limited resource environment owners are operating within, these approaches cannot always be avoided. However, there are a few proven practices that can help owners avoid such severe negative consequences.

How to Do More With Less

The first step in minimizing the negative effects introduced by resource limitations is to ensure that the most leveraging positions are filled by owners and that project team members’ skills and abilities are aligned with the project needs. Business sponsors have the ability and the responsibility to ensure teams meet minimum staffi ng requirements, even if ideal staffing is not achievable. The only reliable way for this to happen is for sponsors to understand the project and the project’s staffing needs. Project teams that have an actively involved business sponsor4 are two times more likely to have owner representation in the most critical functions than projects without active sponsors.

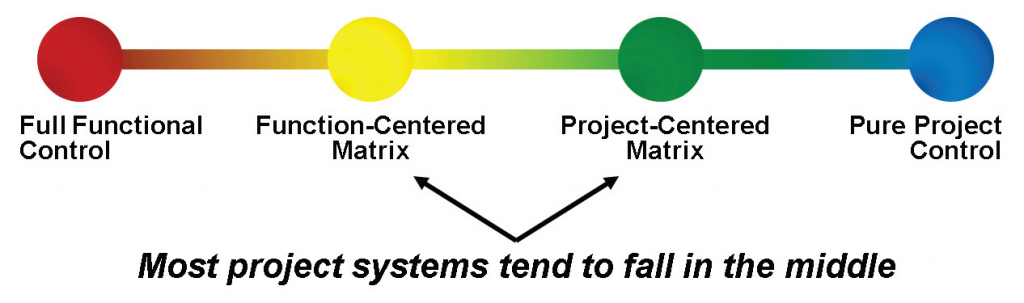

The way project teams are organized also has a big effect on their ability to deal with resource limitations. Project teams tend to be organized in a way that reflects the systems they come from. As shown in Figure 1, systems are generally organized in one of several ways, ranging from full functional control to pure projectbased systems. Most systems, however, are organized as either a function-centered or a project-centered matrix.

In a function-centered matrix, team members report directly to functional leads and the project manager coordinates the work of the functions. In a project-centered matrix, primary authority lies with the project manager; functional leads provide qualified team members and maintain some oversight, but team members report directly to the project manager.

Project teams that cope with resource limitations most effectively tend to be organized in a project-centered matrix. Conventional wisdom suggests that a function-centered matrix allows you to get by with fewer people because some functional strength results from people being housed within their functions and team members are often shared across projects. This, however, is not the case. In a function-centered system, there are inherently more interfaces, and team integration is more difficult to achieve. A project-centered matrix simplifies the flow of information within and outside the team, which eases the problems caused by inadequate staff. Teams that experience resource limitations but still manage to achieve some degree of success tend to be organized in a manner that reflects a project-centered matrix.

Forming the core team early during FEL 2 can also help offset the negative effects of a project’s resource constraints. Teams that experience resource limitations, but are formed early, achieve significantly better project definition than teams that are formed during FEL 3 or later.5 This makes sense because, although these teams do not have all the people they need, they are able to get a head start on the planning process and ultimately achieve better definition.

Several other ways of effectively coping with resource limitations include:

- Leveraging retirees to fill short-term gaps in the project team, especially in situations where they will have the opportunity to impart their knowledge to the next generation

- Establishing and maintaining long-term, mutually beneficial relationships with contractors where individuals from the contractor have the opportunity to develop an understanding of the owner’s standards, processes, and requirements—this can take the form of formal alliances or informal relationships

- Performing targeted development and support of inexperienced owner personnel through mentorship relationships and communication channels with peers

Download: Coping With Resource Limitations on Capital Projects

Improving the Project Staffing Outlook

It is extremely difficult to find enough people who have the expertise required to execute a portfolio of projects. Reasons for this dearth of talent range from the lack of foresight on the part of companies to recruit and develop staff to the “demographic cliff,” a common reference to skilled workers who are retiring without a sufficient pipeline of talent ready to take their place in the workforce. The main reason planning is challenging is because it requires a long-term commitment and a focus on the important, sometimes at the expense of the urgent.

The practices outlined here may help manage this issue more effectively but do not do anything to improve it for the future. To fully address this problem as an Industry is quite complex, but owner companies can take some high-level steps to improve the staffing outlook for their portfolios:

- Define and understand core capital project functions: For each function or functional group involved in capital project execution, identify critical responsibilities and the expertise required to perform them.

- Assess the current state of owner people resources: Use functional definitions to determine the competence of existing resources.

- Assess immediate staffing needs: Conduct workforce planning based on corporate strategy and portfolio planning. With an understanding of functional demands, the type and level of necessary resources can be identified based on the amount of project work and specific characteristics of the work.

- Identify gaps in the current state and staffing needs: Compare the current state of owner people resources and the immediate staffing needs to identify gaps.

- Address immediate needs: Develop a plan to address identified gaps between current and needed internal people resources. If competency gaps are identified in existing resources, create individual development plans to get them where they need to be. If additional resources are needed in specific functions, use functional definitions as the basis for recruitment and selection.

- Assess long-term staffing needs: Strategic workforce planning should be conducted based on long-term corporate strategy and portfolio planning. With an understanding of each function, long-term staffing priorities can be identified and risks mitigated in a targeted manner.

- Plan to address long-term staffing needs: Develop a plan to move internal functional resources from where they are to where they need to be over the next several years. This should include staffing plans and contingencies, clear career paths linked to development plans, compensation structures aligned with strategy and resource needs, and a performance management system that effectively promotes excellence in performance and addresses weaknesses.

To learn more about IPA’s capabilities around capital project organizations and teams, please visit our Organization & Teams page.