Responding to the Oil Price Drop Amidst COVID-19: Lessons From History

In the Roman calendar, the Ides of March simply referred to the 74th day of the year, which roughly corresponded to the 15th day of March. Later on in 44 B.C., the date became notorious as the day when Julius Caesar was assassinated, which marked a turning point in Roman history. The phrase “beware the Ides of March” became symbolic of pivotal moments, or turning points in history, after Shakespeare penned Julius Caesar at the end of the 16th century. In the future, when the history of the oil industry is written, our Ides of March may very well be the 18th of March: the day when the price of a barrel of oil touched the low 20s ($21.20)[1]—a level it had not seen since the 1940s on an inflation-adjusted basis. So let us explore our present situation amid the COVID-19 pandemic and in the wake of, yet another, global oil price fiasco.

The COVID-19 pandemic may very well change social and business practices when it reaches an end. As for lower oil prices, unfortunately—or fortunately depending on whether you are the half-full or half‑empty kind—the oil and gas industry has been in this situation before, albeit today we are facing both supply and demand driven pressures on price. What should our response be?

The actions industry should take may not look all that different from those taken by companies that have become industry leaders following previous sharp market downturns. So let us start by examining our past responses to price crash and examine the consequences of those responses. Below we look back on the industry’s typical responses to previous price drops and then provide information on how those responses have played out. The hope is that we can use the lessons from history and set forth an agenda to avoid making the same mistakes that have repeatedly thwarted industry‑wide progress.

We first examine four broad categories, including our responses in those categories and the consequences. We then offer three areas where the courageous amongst us could do something different this time around.

Category 1: Projects

The most common category, and the one that attracts the most immediate focus, is projects. Projects are either delayed, slowed down, or in some cases outright canceled. While in the short-run canceling a project may appear a rational move to manage cash flow—and let’s face it, projects are easier to cancel than dividends—in the long run, assuming companies still actually care about replacing reserves and production, this is a detrimental decision. Some of the more sophisticated companies, and certainly the ones with stronger balance sheets, may recognize the long-term nature of certain opportunities and continue moving those projects along.[2] A likely challenge to project teams will be to optimize costs. There are some key lessons learned here.

When the oil price crashed in the 2008-2009 timeframe, driven by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), our projects were bloated, meaning we routinely oversized, over-scoped, and over-capitalized our projects. During that timeframe, challenging projects to become more competitive, become lean and fit, to right‑size the scope, was absolutely the right thing to do. Projects would routinely be scoped and estimated at twice industry norms.

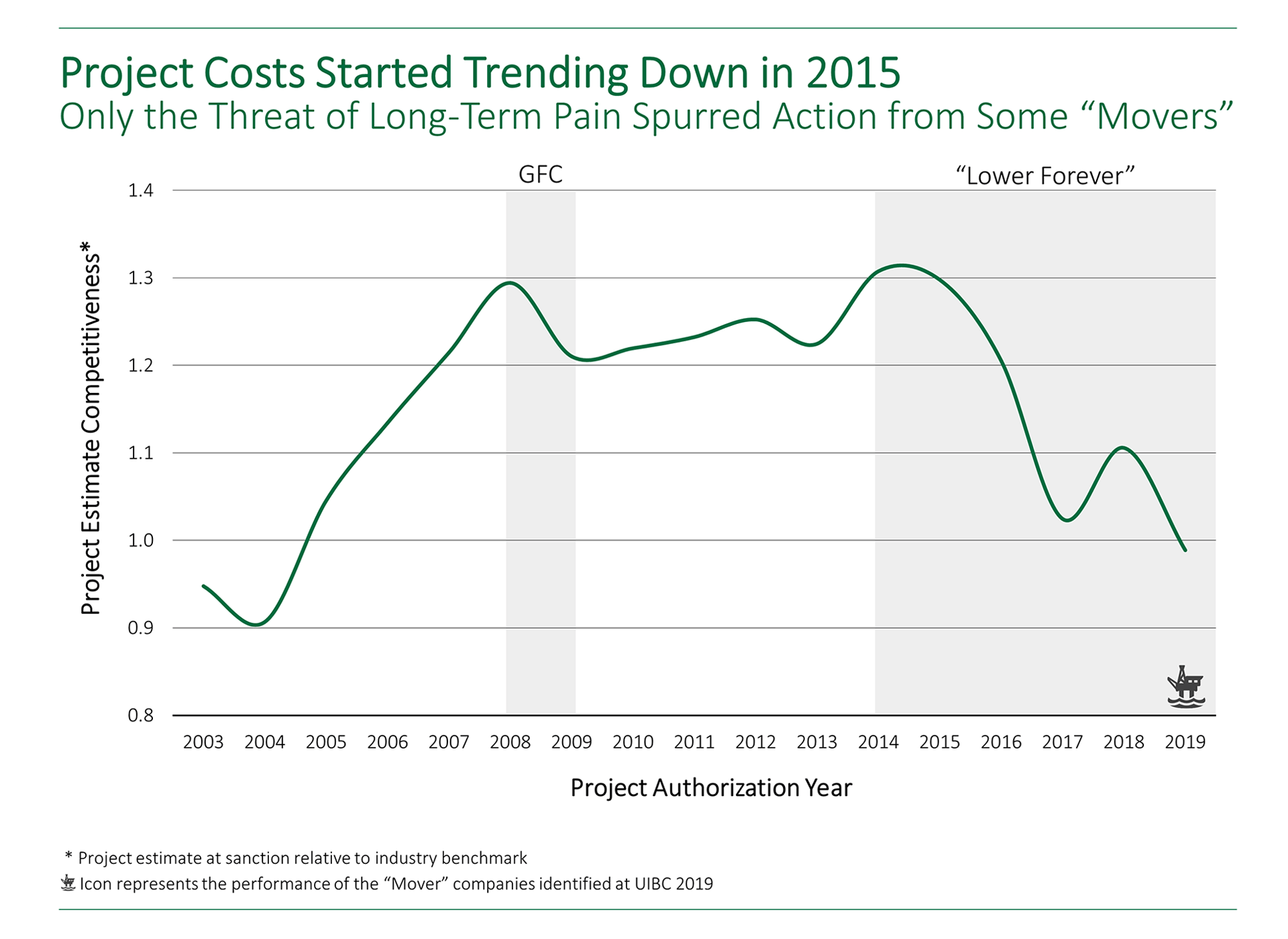

The GFC-driven crash of 2008 – 2009 was Industry’s first warning that oil prices will not stay high forever. A reasonable response then would have been to address the over-capitalization and over-scoping issues in a systematic manner. As Figure 1 shows, however, we barely made a dent—about a 10 percent improvement—but still 20 percent higher than the long-run average. We squandered our first chance. Six years later, in 2014, we faced another price drop, and the industry was right back where it was in 2008 – 2009. Except this time around Industry realized it was entering a lower forever period. Some firms saw this as the right time to pivot the way projects should be done in the face of growing competition from shale, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and renewables.

At the annual gathering of the Upstream Industry Benchmarking Consortium (UIBC) in 2019, three companies—the movers—responded brilliantly and lowered their project CAPEX, on average, by 30 percent. It is important to note this 30 percent reduction in project capital cost is after accounting for deflation in costs and price reductions and renegotiations that came from the supply chain (more on that later). Because of previous cost pressures in the 2008-2009 timeframe, achieving another 30 percent reduction was a much tougher challenge, and it took these movers the better part of 3 – 4 years to get there; in other words, achieving structural changes to make lasting cost improvements is not a 6-month affair. It requires deliberate planning with targeted areas and data-based decision making. Many other companies still have not achieved those changes and will be the ones struggling to recover properly from this period of sharply lower oil prices exacerbated by constraints due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

IPA data show that other industry players, in addition to the movers, are on track to develop projects at 10 – 30 percent below long-run industry norms. But because these companies waited too long after the 2014 price drop to make structural changes, this double whammy may set their efforts back substantially. But by and large, project teams do not have much CAPEX to give without sacrificing safety, quality, or functionality. The projects struggling with uncompetitive costs are in this situation either because their firms have not made the structural changes needed or the opportunities were never attractive to begin with (more on that later also).

Category 2: Supply Chain

The next most common area to go looking for cost savings is the supply chain. Similar to projects, the supply chain in the 2008 – 2009 timeframe had a lot of room to give. It is important to note, however, that during that timeframe, supply chain prices increased because of the demand in project activity. The oil and gas supply chain had been steadily weakening even prior to 2008, leading to high prices with increased demand, since enough capacity was not available. Since then, the supply chain has grown weaker still. Suppliers had to provide discounts and renegotiate contracts during the 2008 – 2009 timeframe, and in some cases, according to IPA data, we see that supply chain costs decreased by 15 – 25 percent—more in subsea and FPSOs and, to a lesser extent, in other areas too.

But another significant consequence of our historical decisions has been that many players in the oil and gas supply chain either shuttered or divested from the oil and gas sector, including filing bankruptcy. Bankruptcies and divestures that stem from these bad decisions continue to play out today. Sure, new yards in China have provided some diversification, but nevertheless the supply chain does not have enough capacity to meet the demand. In fact, as the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed, several industry projects all fabricated in China or Far East yards are now exposed to potentially cascading delays. Why? Because we all use the same few yards and, therefore, are constrained by the same few critical resources.

Challenging suppliers to cut costs under the we are all in this together narrative will not yield much effect. Yes, some suppliers can ostensibly provide some savings to owners in the short-term, but given the oligopolistic nature of many supply chain elements, these savings will be short lived and may, in fact, become premiums as soon as the activity rebounds. Furthermore, project delays are already going to make some suppliers and vendors vulnerable. If any more of them go bankrupt or leave the sector, it will make an already‑weak supply chain situation dire. This is particularly true for smaller vendors, smaller fabricators, and engineering shops. So where we are now is that the market will not be able to give back a lot of costs, if any at all. It is fairly certain that, when the current crisis is said and done, the supply chain will become even more consolidated and weak. In the long run, the effective costs of our projects are likely to go up due to quality and capacity issues.

Category 3: People

So far, we have not seen mass layoffs in the industry—owners or suppliers—and this is a good thing. Remember, people do projects. In the past, price downturns in the industry caused projects to shed many people. [It is worth noting that IPA’s Organizations and Teams practice is one of our busiest practice areas, because frequently we are called upon to help develop competency and capability plans.]

Decisions to downsize project capability in the past have created a long-term capability challenge. Companies have had a difficult time finding and/or developing the skills they need, especially in core project capabilities.[3] The weakness of competencies, skills, and capabilities is evident in the error rates in engineering drawings, quality issues in construction, and basic mistakes in quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC). Today, IPA is aware of a number of projects experiencing severe startup and ramp-up delays due to construction and engineering quality issues exacerbated by poor-quality QA/QC.

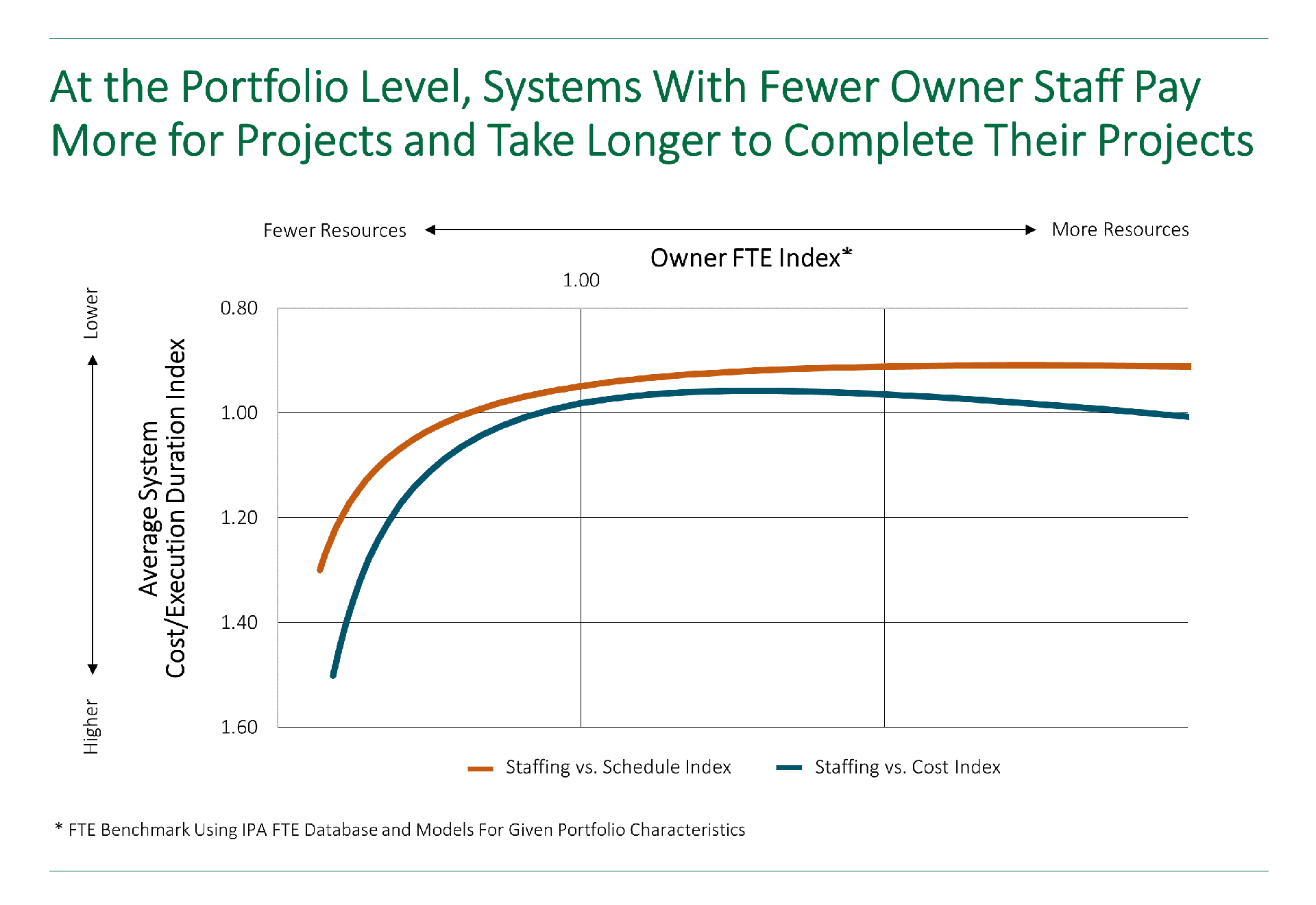

While taking a hard look at and potentially right‑sizing staff (in line with a leaner and fit‑for‑future portfolio) is the right first step, historical decisions would suggest not much room is left to give on the people side of Industry in general. Figure 2 shows too many or too few owner resources can be detrimental to the cost and schedule performance of project portfolios. And decisions about capability made today based on the short-term outlook need to be taken seriously because they will have lasting effects as evident in the current environment. This is certainly true on the supplier side and even more of an urgent issue for them. Owners often pull from suppliers for the people/skills they need leaving the suppliers vulnerable. Considering projects are fighting a shortage of talent across owners and suppliers, owners are increasingly facing serious issues in the form of quality problems in execution.

Category 4: Portfolio

Looking at our portfolio makeup is a good place to look for cost savings for the long term. One way some leading UIBC companies improved their cost competitiveness was to take a hard look at the basket of opportunities they were pursuing and shed opportunities that had no chance of becoming competitive and profitable projects. Leading up to the GFC, development cost per barrel ($/BOE) was creeping up to a point that we would routinely pursue opportunities 30 – 40 percent more expensive than long‑run average. This never made sense but could be justified with the high oil price. But this behavior did not really abate until 2015 when some in the industry finally looked at the opportunity attractiveness issue.

An opportunity with great big reserves but that is in a very difficult location or under very challenging context is unlikely to become a competitive project; most oil and gas companies have such opportunities in their portfolio and now would be a good time to get rid of them. In fact, if there is any silver lining to this period, it may be that owners are forced to take a cold, hard look at projects and accept the stark reality that some opportunities are just not good enough. These projects have to be cut loose. Portfolio optimization is also the biggest opportunity to look for projects that can be done fast, competitively, and take advantage of the digital revolution. Also, owners may consider more standardized and repeat‑type projects than one-offs.

Looking Forward

So given this historical context, what could we do today to improve capital investment outcomes? Are tools and responses available to us that work? Let us explore a few alternatives, while all of these responses require companies to be courageous and are even contrary to what their peers may be doing. Of course, being courageous under shareholder pressure and constant media attention is not for the faint of heart, nor those with weak balance sheets. These responses are not hypothetical—they have been put to use successfully in the past by a few courageous teams.

- Projects—most large projects in Industry take about 7 – 9 years from discovery to first oil/gas. One implication of this is that any project authorized in 2020 will not start up until at least 2024 or later. So, if a project is competitive, this would actually be a good time to continue with the project or at least position the project to be prepped and ready at the starting line. In doing so, as soon as the rebound occurs and pandemic‑related constraints are lifted, these projects can move quickly and smoothly into execution. A consequence of not having this worked out—on a project‑by‑project basis—is that when a rebound does occur, everyone will want to get their projects in queue with suppliers, vendors, and yards, creating heavy demand on capacity that will lead to price spikes. In fact, this period might even be the right time to work with the supply chain to find symbiotic ways to keep the supply chain healthy, productive, and resilient. This will prevent current stresses from morphing into catastrophic issues. Remember several successful examples of collaboration with the supply chain and coopetition within the sector exist outside our Industry.

- Improving Work Process Efficiency—while many in the industry worked hard to improve projects’ competitiveness, as discussed in earlier sections, the same cannot be said about schedule, especially early phase schedules. As an Industry, we are extremely inefficient between discovery and end of scoping. The forced slowdown in our work actually serves as an ideal time to take a hard look at our work processes; stage gate requirements; deliverables; and, in general, the work and information flow in the front-end to identify opportunities for making the front-end more efficient. IPA analysis clearly demonstrates that most companies can harness 20 – 35 percent efficiency improvements in the front-end durations. To be clear, we are not advocating speed at the expense of robust gate packages. But our data are clear that information flow has become inefficient; while the underlying reasons are different in different companies, it is time we find ways to make information flow more efficient. It requires a lot of courage to reexamine the way we work. It will also require killing a few sacred cows and, more importantly, it will require a pivot from being simply deliverable driven to efficient flow of information driven. Data analytics and digitalization should help in this area.

- Digitalization—Prior to the price crash, digitalization was everywhere; everyone was investing in new technology, all in the hopes of harnessing the productivity, efficiency, and agility in decision making promised by this new trend. [And yes IPA truly believes in the benefits of digitalization and the efficiency gains possible from it]. Forced self-isolations and work‑from‑home conditions have put some aspects of digitalization to the test. IPA has heard from many clients that connectivity with colleagues, video conferencing in large groups, and general business continuity have proven the value of technology.

However, when asked whether digitalization has enabled better access to information for project teams or produced measurable improvements in productivity, enthusiasm is muted. The dark cloud surrounding our connectivity success is that many internal digitalization initiatives have only just begun. Complicating matters, there’s a limited pool of capital for digitalization investments which are also in competition with other projects and initiatives for funds. Meanwhile, some companies are being forced to face the reality that many solutions are not really delivering on the nirvana promised, not because these initiatives are failing but, rather, because some technologies remain immature and many digital initiatives lack clear, coherent objectives. And because of these unclear objectives, some digital initiatives are not progressing in the agile manner expected.

But why is it that over the past 30 years, we have seen zero improvement in engineering and construction labor productivity? The answer is in the data, which we do not have. The challenge facing Industry isn’t the pursuit of technology, it’s the accessibility and quality of data that makes the technology useful and digitalization initiatives successful. What data we do have is horded away in silos—sometimes by accident, sometimes on purpose. Regardless, we need transparency. We need to see, in live data streams, why engineering is always late. We need to see, in live data streams, why construction tool time is 30 percent. Combined, these competencies make up half our project costs. Were we to improve our productivity in these areas by 10 percent, we lower our CAPEX by 5 percent. Five percent is not a huge number, but it is doable, and if we really sort out the drivers of productivity through bonafide data, it is sustainable. So should we be slowing down or canceling our digitalization efforts? Of course not. But we do need to focus them on the levers that provide the most return. The courageous should take advantage of the extra time we have. Get the domain experience into a room together and hash out what is needed to answer these questions that have eluded us for so many years. In fact, now is the time to double our efforts in digitalization, not scale them back.

None of the solutions presented here are earth‑shatteringly new or novel per se; they are novel in the sense that we have not usually tried them in prior crises. But hopefully they provide ideas and, more importantly, some context for our previous actions.

“Today is only one day in all the days that will ever be. But what will happen in all the other days that will ever come can depend on what you do today,” as Ernest Hemingway wrote in For Whom the Bell Tolls. We do not know exactly how long this crisis will last or how it will end. But if there is anything we know from the past crises and our response as an Industry, it is that we plant the seeds of the next crisis in today’s crisis. The competency and skills problems, the weak supply chains, the difficulty of accessing our own information, and many other issues we face today are all problems we created for ourselves through our decisions in prior crises. The question facing us now is whether we will apply the same playbook of the past or will someone be courageous enough to take this moment and really pivot and transform their organization completely by working to make the organization flexible, resilient, and adaptable to work in a non‑traditional business environment.

IPA is committed to assisting owner companies across all industrial sectors with their projects and project systems as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds. As part of this effort, IPA leaders and subject matter experts will continue to publish articles like this one explaining how business and project managers may choose to address some various project development and execution, contracting, organizations and teams, remote work, and other industry topics stemming from the global disease outbreak. Energy companies searching for direct and immediate guidance as to how they can strengthen their project portfolios and systems are encouraged to reach out to IPA.

[1] Tim McMahon. “Historical Crude Oil Prices: Oil Prices 1946-Present,” Inflationdata.com. Updated April 8, 2020. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://inflationdata.com/articles/inflation-adjusted-prices/historical-crude-oil-prices-table/.

[2] Although recent announcements suggest this may not hold true for larger companies either.

[3] Lucas Milrod and Sarah Sparks, “Making Intentional Staffing Decision to Preserve Core Owner Functions,” Independent Project Analysis, April 3 2020, Accessed April 16, 2020, https://www.ipaglobal.com/news/article/making-intentional-staffing-decisions-to-preserve-core-owner-functions/.