Risk Identification Lessons for Capital Projects

All capital projects face risk—and some face risk of events that can derail the whole effort, leaving the company worse off than if it had done nothing in the first place. Why is the consequence of these risky events—catastrophic or not—so hard to foresee? Why is it so difficult for companies to plan for and mitigate against capital project risks? What should the risk identification process look like?

What Are Project Risks?

Before we can answer those questions, let’s look at what risks are in the context of capital projects. Project risks come in many forms. Risks can be technical or non-technical. They can be political, driven by new or existing rules and regulations, or the result of supply chain breakdowns or skilled labor shortages. Some are easily anticipated—like the risk of implementing new technology—though the magnitude of what can go wrong is often underestimated. Others are hard to foresee—like a global pandemic.

Projects face different risks as they progress from business idea to definition to execution and startup. Risks in the business planning phase might involve getting on the same page as other participants in a joint venture or securing a buyer for the intended end product. During project definition, failing to identify the project scope and fully define it raises the risk of errors and changes later in detailed engineering and construction. When a project moves into construction, it faces risk of lack of skilled labor, strikes, and adverse weather events, among many others.

Why Do We Fail to Identify Project Risks?

Identifying risks—at all stages of the project lifecycle—is difficult for many reasons. In the business planning phase, early in project lifecycle before the execution team is assigned, it is hard to anticipate what problems the project might face in execution—or even later in startup. In addition, at this early stage, we tend to dismiss future risks, thinking they won’t happen to us or to our project. In the absence of data, humans do err on the “we can manage it” side—a phenomenon known as optimism bias. However, this is the best time to identify showstopping risks the project may face in future phases. The earlier these risks are identified, the sooner companies can determine whether the project is in fact viable. Discovering them later in the project life cycle leads to higher sunk costs.

In addition, the risk assessment process itself is flawed. The focus of risk identification is often too narrow, does not involve the right people, and is done in the absence of solid data. Sometimes, team members lack the experience needed to fully identify risks. As a result, the process often does not identify show-stopping risks at the earliest possible opportunity to identify threats to the viability of the future asset or project.

Finally, few companies take the time to analyze their projects after they are completed to derive lessons learned that can be used to improve the outcomes of future projects in their portfolios. Often the team members have moved on to other projects before a lessons learned workshop can be conducted. For companies that do take the time to collect lessons learned, organizing them so they are easily accessible and useful for future projects often proves difficult.

IPA’s Approach to Risk Identification: Using Lessons Learned From Past Projects

To help companies identify risks that a planned project faces—independent of internally identified risks—IPA looks to the risks identified, and the risk outcomes, for similar projects. This is difficult for an individual company to do but possible for IPA given our extensive database of past projects, including detailed histories for the projects we analyze. Our projects database includes extensive information for each project we have analyzed, including critical driver metrics, execution plans, cost estimates, field development plans, and native schedules, as well as the detailed and sequential history. An IPA project risk evaluation uses those detailed case histories for completed projects, and related relevant research, to quantify the effects of certain incidents on outcomes.

Using IPA’s database, we can investigate the frequency and effect of these actual project incidents on the project’s cost, schedule, and ultimate success to understand how they affected similar projects and provide relevant mitigation strategies based on our historical experience with similar projects.

Case Example: Evaluating the Risks Similar Projects Faced to Assess Current Risk

An oil & gas client planning a complex onshore/offshore megaproject came to IPA attempting to avoid the poor outcomes that had occurred on its other past projects. The goal of this engagement was to identify the risks this planned megaproject might face to implement relevant mitigation strategies and achieve successful project outcomes. To support this company’s effort, IPA looked at the lessons learned from similar projects to determine what risks they faced, how they did (or didn’t) mitigate against those risks, and what effects these risk incidents had on the projects.

To start, we drew a sample of similar projects from our vast database of projects to understand the risks similar projects experienced and the effect those risks had on project outcomes. From this group of similar projects, we created a register of incidents, which included the incident description, cause, quantified incident effects, and mitigations. We used the detailed information we have for each project in our database (collected as part of every project analysis) to support this effort.

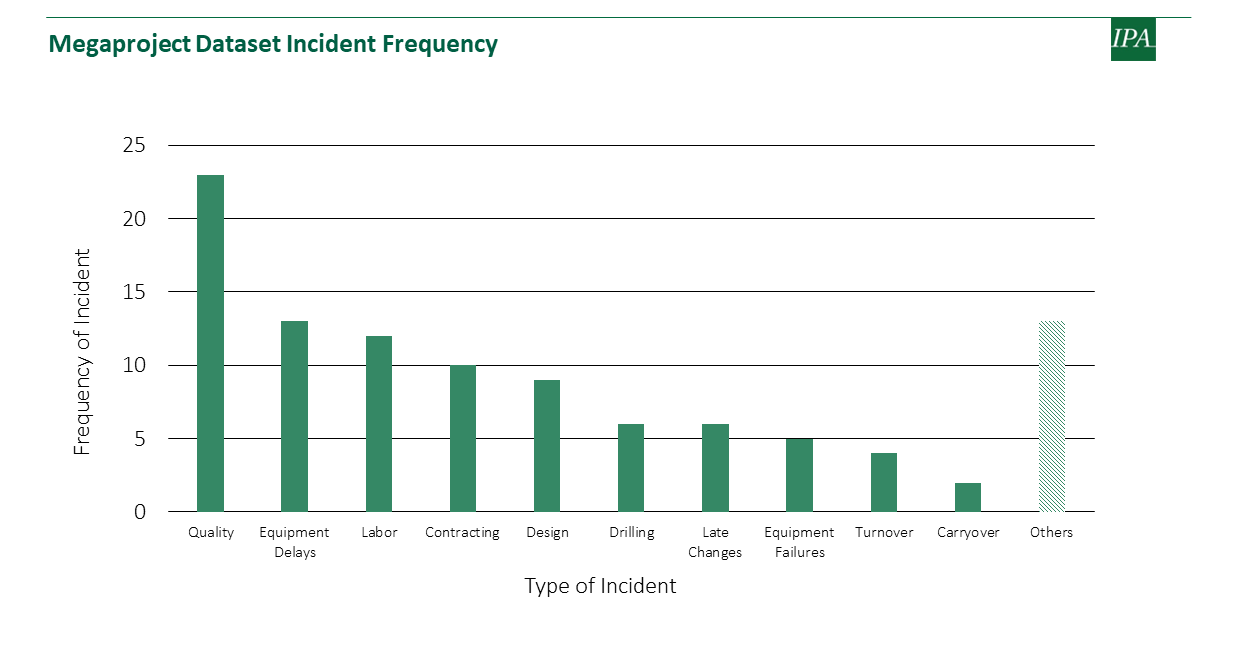

IPA then sorted the incidents and their causes into themes and analyzed the distribution and frequency and the cost and schedule effect of each incident theme (see below).

Overwhelmingly, the most frequent incident types historically applicable to this type of megaproject were quality-related, followed by equipment delays and labor-related problems. Failure to meet quality requirements can have serious consequences for any project. Companies need to have mechanisms in place to ensure project requirements are met. However, even with standards in place, quality problems can arise. From the selected dataset of similar projects, we identified more than 20 projects that had quality-related issues in engineering, installation, equipment configuration, or inspection. On average, the effect of quality-related issues was schedule slip of 8 months.

One example of a quality incident is construction delays that arose because rigorous equipment quality assurance was not done. The team depended heavily on contractors for factory acceptance testing (FAT) and quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) inspections, lacked an owner quality process, and relied on inexperienced contractor personnel. Having dedicated FAT personnel who can create structured, owner-led equipment testing regimes mitigates against this risk. These personnel must ensure QA/QC expectations are understood and that the FAT outcomes are addressed in the contingency plans.

Complete the form below for more information about how IPA can help your company with risk identification for capital projects.