Shaping CCUS Opportunities Requires Diligence

Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) is emerging from the shadows after years of promise but little investment. Capital spending on CCUS technology is recognized as critical to achieving net zero emissions goals. Significantly, companies that had been sitting on the fence now have CCUS firmly in their business strategies and are preparing to invest billions: new CCUS capacity in development has more than tripled in the last 3 years, and is expected to deliver twice the capacity of the 26 facilities already in commercial operation globally [1]. These projects must pave the way for many more: The International Energy Agency’s Sustainable Development Scenario has the amount of CO2 captured growing by a factor of 20 in the next 10 years [2]. A bold target, indeed, if we aim to achieve it.

Many corporate leaders, recognizing the strategic need for CCUS technologies, now face this challenge: will our proven capital project development and execution model also deliver success for novel CCUS projects in an unfamiliar context? In completing project risk evaluations of half of the currently operating large-scale CCUS projects, Independent Project Analysis, Inc. (IPA) has found wide differences in the use of known Best Practices—and in cost and schedule outcomes. This article is the second in a series introducing the key factors that drive success in CCUS projects, based on learnings from these evaluations and other projects with similar complexity. The first article covered the need for clear business objectives. This article focuses on how we shape an opportunity to enable these business objectives to be developed into an executable project. We will identify particular shaping complexities that CCUS projects face, and answer this central question: Does the imperative to deliver CCUS projects justify a different approach to opportunity shaping than the established Best Practice for megaprojects?

Opportunity Shaping Challenges for Integrated CCUS

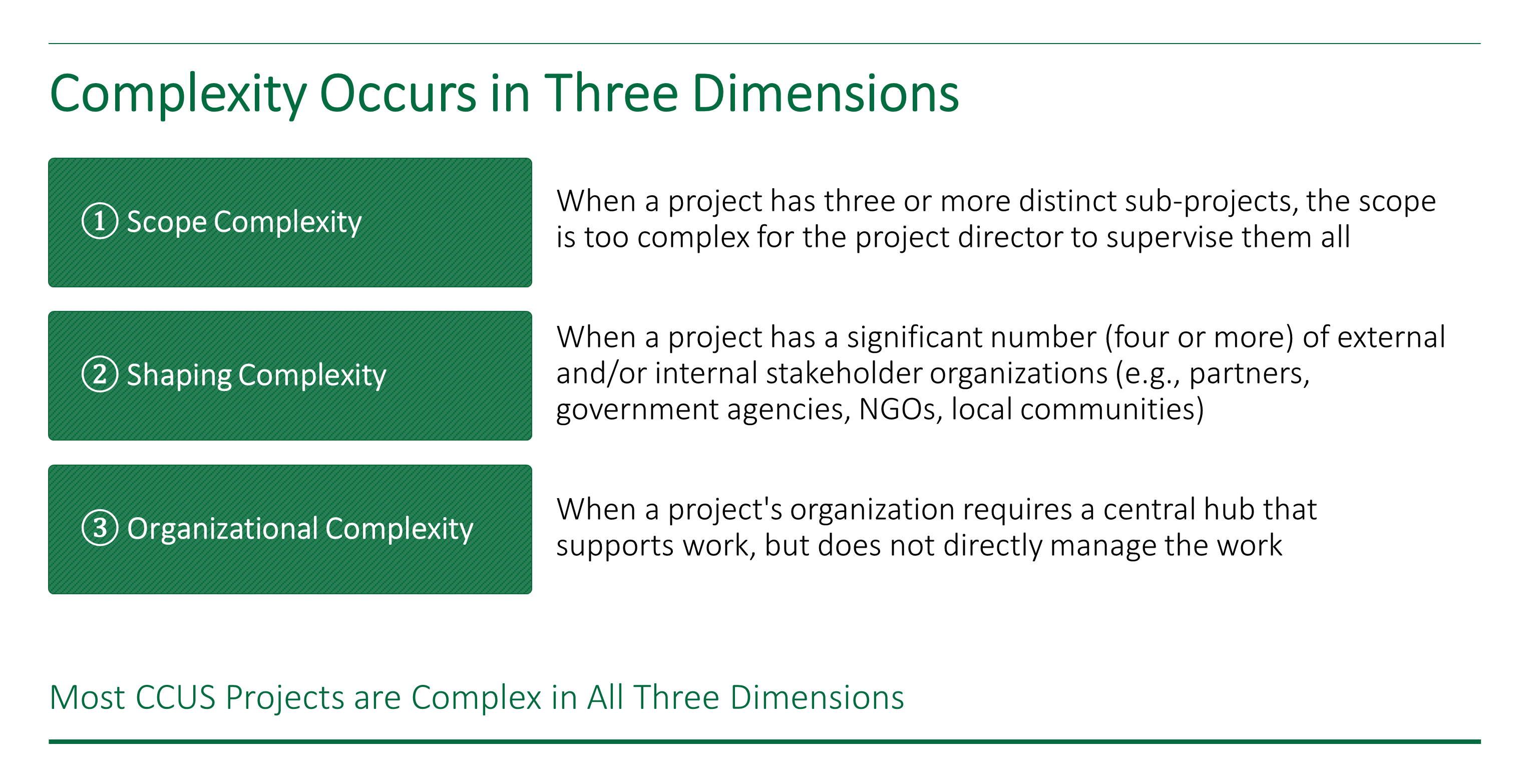

The first article in this series, advocating clarity in business objectives for CCUS projects, explained how the multiple technical and organizational interfaces common in integrated CCUS projects, and an often untested and fluid regulatory and financial environment, give these projects a shaping complexity that can put them in megaproject territory—even when the capital cost is relatively modest (Figure 1). Note that this complexity is rarely technical. The shaping challenges reviewed in this article consider breadth of scope and in particular the novelty of the business proposition: capturing CO2 from anthropogenic sources, transporting it, and storing it permanently underground, often within a wholly unfamiliar commercial model.

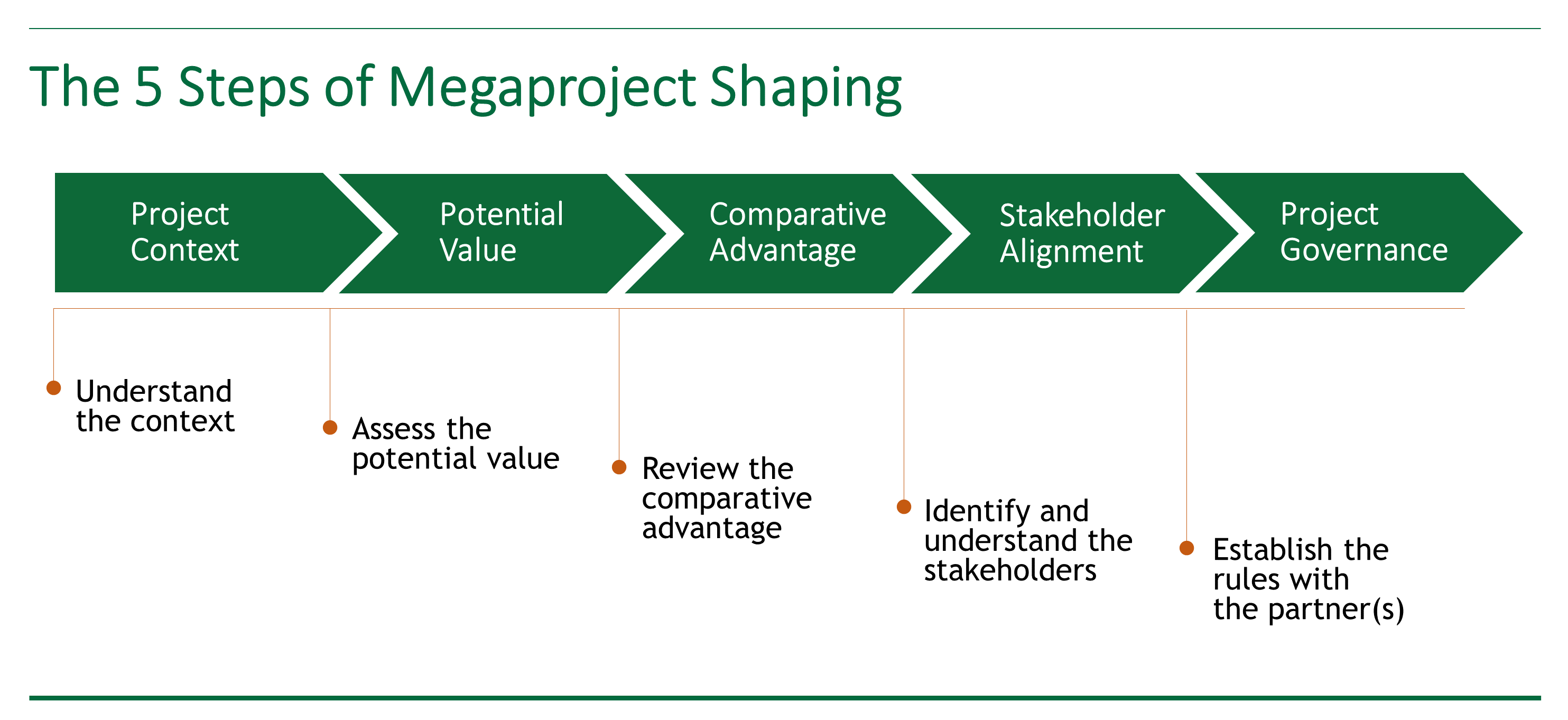

What do we already know about megaproject shaping? As IPA Founder and President Edward W. Merrow explains in his seminal book, Industrial Megaprojects, good megaprojects start with a business-led process that allocates project value among the stakeholders to fashion a project environment stable enough for successful execution while meeting the sponsor’s objectives. This process of evaluating key project attributes, gathering the information needed for key decisions, and allocating project value is what we call shaping. Shaping can be conceptualized in five key steps, illustrated in Figure 2. These steps must be completed by the end of the scope development phase (FEL 2) of our project process if later phases are to have a strong chance of success.

The following CCUS project characteristics pose particular challenges as we follow this shaping framework.

Regulations Are Fluid

An important objective of understanding the project context is mapping the regulatory landscape and assessing its stability. Merrow’s research found that permitting problems, such as when permits are delayed or withheld, or when permitting requirements change repeatedly, are encountered by 20 percent of megaprojects. Permitting problems cause these projects to really suffer: they had double the average execution schedule slip, four times higher cost overruns, and more prevalent operability problems when compared to the 80 percent that avoided permitting problems [3]. If a primary purpose of shaping is to calm the turbulent environment enough for smooth execution without serious damage from that environment, the shaping process for these 20 percent of projects can be said to have failed fundamentally.

But regulations covering CCUS—including transportation, injection, and long-term storage liability—are in transition in many jurisdictions; in others, laws have been passed but are yet to be tested. Some CCUS projects may have as an explicit objective to demonstrate a navigable path through new national and international regulations, reducing the risk for investments that follow. In these cases, a deep practical understanding of the regulatory climate, and the clearance of permitting hurdles, are not just enablers of smooth execution—they are outcomes to be valued in themselves by the project sponsor. Pioneering CCUS sponsors may need to take regulatory shaping further yet: identifying where necessary regulation is missing or outdated, and through their advocacy and expertise leading efforts to drive forward new laws, enabling their project and others to move ahead [4].

Accordingly, whereas in more conventional projects the influence of permitting on the critical path may be the project director’s sole interest, for CCUS projects, regulatory issues have a broader significance, and call for a tailored approach.

First, we must start understanding the regulatory constraints from the start of shaping a CCUS opportunity, but nonetheless accept that regulatory uncertainty may remain later in project definition, and even execution, than we would normally accept. This demands rigorous assessment of regulatory risk, and clear alignment with project and CCUS-chain partners, investors, and internal stakeholders on how that risk will be treated at key project decision points. Secondly, the significance of regulatory activities to achieving business objectives must be clearly expressed to ensure that the necessary resources are available to the project, and to ensure that decision makers’ tolerance of regulatory risk reflects that significance. Finally, instigating regulatory change will likely need to be started long before it is required, and will require owners to organize their efforts from the top of the company down and from the project team up. These challenges will almost always justify the inclusion of a dedicated permitting and regulatory affairs representative on the project team.

Potential Value Is Unproven

In most jurisdictions, the price of emitting CO2 is still lower than the cost of capture, transportation, and storage. CCUS schemes, therefore, usually rely on national or transnational subsidies or other financial incentives to demonstrate a viable business case. (Although some CCUS projects to extend the life of a carbon-intensive facility that would otherwise be a stranded asset may be fully justified by the continued income from that facility.) Government incentives are subject to change as administrations seek mechanisms to deliver evolving climate policy, and as a result, CCUS business case shaping must often make considerable assumptions about carbon pricing over the life of the facility.

Additionally, some CCUS projects—most obviously hub and cluster concepts—aim not simply to create capital assets that will deliver a return, but also to create an entirely new business. This adds further uncertainty to the early business case. Establishing the feasibility of such ventures can be challenging for industry decision makers, who are used to having high confidence in the value of a conventional sub-surface resource to be exploited and an established market to be served. A CCUS project aiming to create a new business may not be able to follow our normal decision making frameworks, which require business case closure before starting FEED. When planning CCUS opportunity shaping, we should recognize when business development and scope development must mature in parallel, up to and even beyond a final investment decision (FID).

This has implications for the way we approach our assessment of the potential value of such projects. If we measure success by the influence a project has on future CCUS development, as well as the intrinsic value returned by the project, then we must ensure that definition of value is recognized by internal business stakeholders. This value model will likely be more complex and harder to quantify than IRR alone, and rely on measures of application, diffusion, and information success, as well as traditional measures such as the CAPEX and operability performance of an asset. Getting our value model right will ensure we focus our shaping efforts throughout FEL on meeting the true strategic business needs.

This will also likely mean more business and commercial development functions within an integrated CCUS project team than we would expect based on the scale and complexity of the technical scope, and we should accept that staffing costs for opportunity shaping and business development throughout FEL will be correspondingly higher.

Stakeholder Engagement Is Critical

CCUS projects come with many stakeholders, and potentially significant external interest. These stakeholders may operate outside the owner company’s usual range of influence and expertise. However, they can be critical to a project’s success. External stakeholder relationship-building and broader public relations efforts must go hand in hand with the regulatory and business development shaping activities discussed.

This can involve a considerable workload for a team shaping a CCUS project. IPA interviewed one CCUS project team in a critical development phase that found itself giving an average of two external presentations per day. It goes without saying that few owner teams, even for megaprojects, are set up to coordinate this level of stakeholder attention and keep stakeholder claims on project value sufficiently aligned with the project sponsor’s interests.

CCUS projects also tend to involve several partners or stakeholders within the CCUS chain, with potentially conflicting agendas that cannot be assumed to be aligned. Examples include: emitters looking to install CO2 capture at minimum cost, transportation providers trying to maximize infrastructure utilization and expand service provision, operators keen to repurpose legacy production assets for CO2 injection rather than bear disposal costs, and storage liability holders obliged to limit long-term risk. All of these stakeholders must be brought onboard with coherent aims for the project, and the timing of their commitment to the project must be carefully coordinated to allow progress.

If we accept that regulatory and business case uncertainty may extend beyond completion of scope definition, we should nevertheless contemplate no such delay with stakeholder management. Stakeholder engagement should be actively pursued with adequate resourcing in the owner team from the start of shaping. It should not wait until scope definition is underway.

Project Governance Must Not Be Neglected

Establishing the governance rules with project partners is another shaping task that should not be allowed to drift into late FEL (although IPA sees this often). If a CCUS project will be executed through a joint venture (JV), it is tempting for the partners to delay agreeing to the framework for JV operation until the rest of the opportunity is fully shaped. This is a mistake. IPA research into the drivers of success for JV projects identified important practices that improve cost and/or schedule performance. These include, for example, completing the JV agreement before FEL 2 and agreeing on a process for managing interfaces among partners and with the project team [5].

Without differences in CCUS project partner aims being aired and resolved in a JV agreement, business objectives and trade-offs cannot be clearly and reliably defined. The dependence on potential non-JV CCUS chain members, regulators, and other external stakeholders will likely add enough complexity to the project development and approvals processes: there is no sense in making these processes even more difficult by not having governance rules agreed between the partners and in place beforehand. Uncertainty in JV structure and governance can also make the task of planning execution and operation unnecessarily trying.

Conclusions

Let us return then to our question: Does the imperative to deliver CCUS projects justify a different approach to opportunity shaping than the established Best Practice for megaprojects? The answer is a qualified Yes. The need to forge ahead in some cases in a changing regulatory context and with an unproven business case does challenge our application of shaping Best Practice. A CCUS project may not be able to close these issues in in the scoping phase of the project. We should recognize that this increases the risk of instability during project definition, and requires the application of rigorous “what if” scenario planning to help maintain progress and reduce disruption if plans or project parameters need to change.

The size and organization of the CCUS Project team is critical to success. The team requires additional and dedicated resources to manage these riskier areas of shaping, and assigning clear responsibility for ongoing shaping must be done early in the project development. These resources should be integrated under the Project Director to avoid misalignment of business development and scope development workstreams.

Acceptance of greater risk in some areas of shaping is no excuse for needlessly increasing risk by neglecting others. In particular, stakeholder alignment and project governance must be addressed early and rigorously.

Finally, we have learned that by necessity some aspects of the CCUS project environment are less stable than we would like, increasing the risk of scope and design changes late in FEL and into execution. However, we must not compound that risk by authorizing projects with incomplete project scope definition or weak execution planning. Opportunity shaping may bring unique and exciting challenges early in CCUS projects, but we must not lose sight of the fundamental imperative to deliver assets that operate safely and at full design capacity, on time and within budget, and to guarantee these we should also apply all we already know about project Best Practices in FEL and execution.

The third in this series of CCUS articles will share learnings from similar technology scale-up challenges. To learn more about how IPA can improve the predictability and competitiveness of your company’s CCUS project, please contact us by completing the form below.

[1] Global CCS Institute, The Global Status of CCS: 2020, November 2020.

[2] International Energy Agency, CCUS in Clean Energy Transition, iea.org, September 2020.

[3] Edward W. Merrow, Industrial Megaprojects: Concepts, Strategies, and Practices for Success, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. April 2001.

[4] For example an amendment to the international London Protocol, enabling transboundary movement of CO2 for storage, which was eventually adopted in 2019 following advocacy by the Dutch and Norwegian governments on behalf of particular CCUS projects.

[5] Phyllis Kulkarni and Kelli Ratliff, Best Practices for Joint Ventures, IBC 2004, IPA, March 2004.