Should Project Teams Be Prepared for Construction Shortages in Western Europe?

Before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted global and regional capital project markets, owner companies were reporting stretched construction contractor availability in Western Europe, according to Independent Project Analysis (IPA) data. Evidence of shortages in construction labor and materials supplies in Western Europe prior to the pandemic is worthy of closer examination. For now, with the much anticipated widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines on the horizon, there is cautious optimism that capital project markets will rebound. But could owners sponsoring projects in the region be in store for a choppy industry construction market when the pandemic subsides?

Based on information from IPA’s capital project database, capital expenditure by the process industry was largely stable over the past years, indicating flat demand for capital project resources. Reported wages and escalation were also stable, with the notable exceptions of the areas around Antwerp and Rotterdam. Further, the frequency of project teams reporting shortages related to labor or material availability was global average. However, some segments of the region’s construction market were becoming strained, according to information collected by IPA for project evaluations.

Increasing Construction Shortages

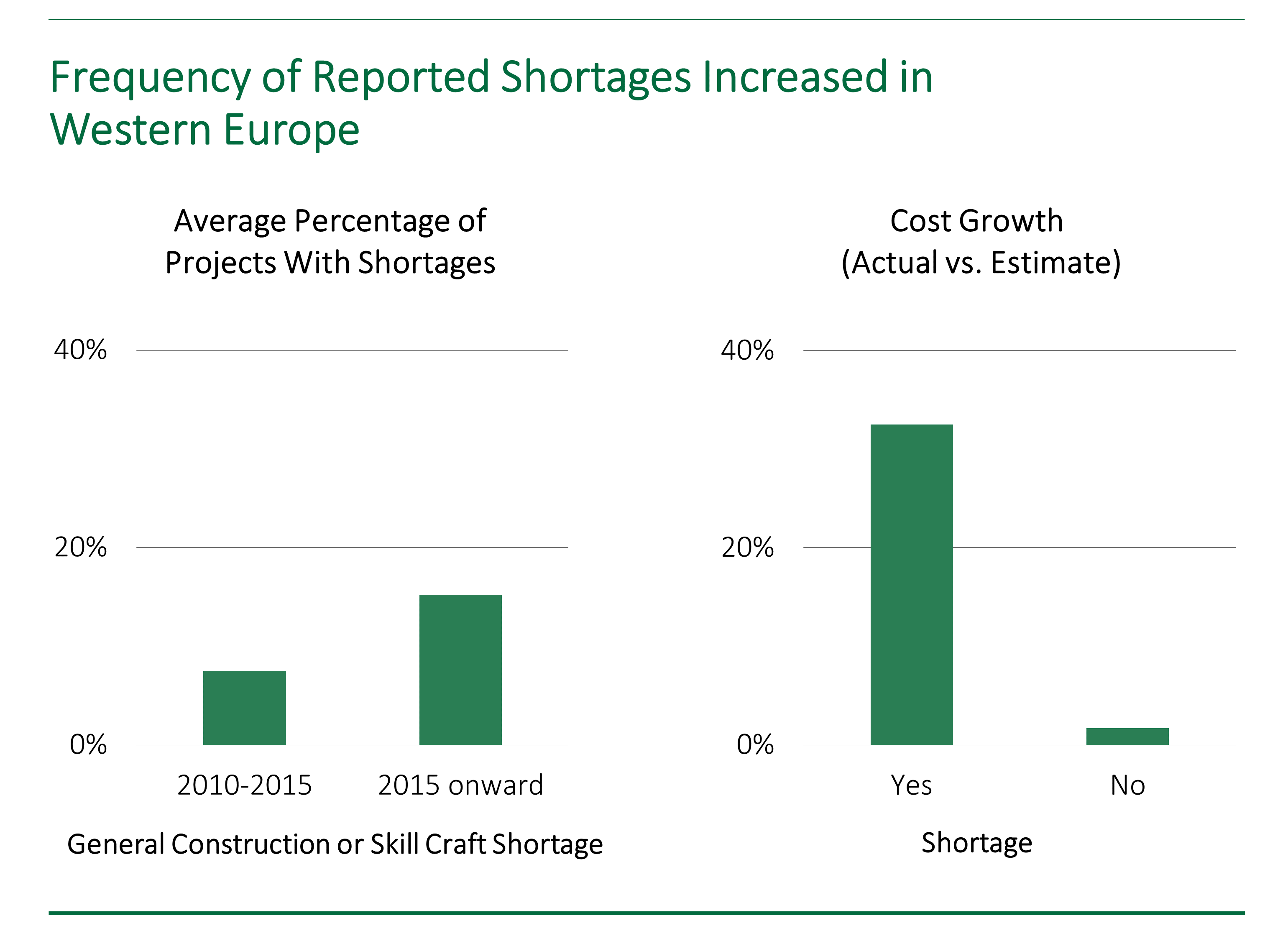

Between 2015 and early 2020, just before the pandemic hit, about 15 percent of projects costing above €10 million and located in West European countries reported experiencing shortages in either labor or materials. Similar-sized projects in other global regions were reporting close to the same percentage of shortages. What stands out about the construction market in Western Europe, however, is that the percentage of projects reporting shortages doubled compared to the previous five-year period. Many of these projects that experienced shortages suffered from large cost growth (Figure 1).

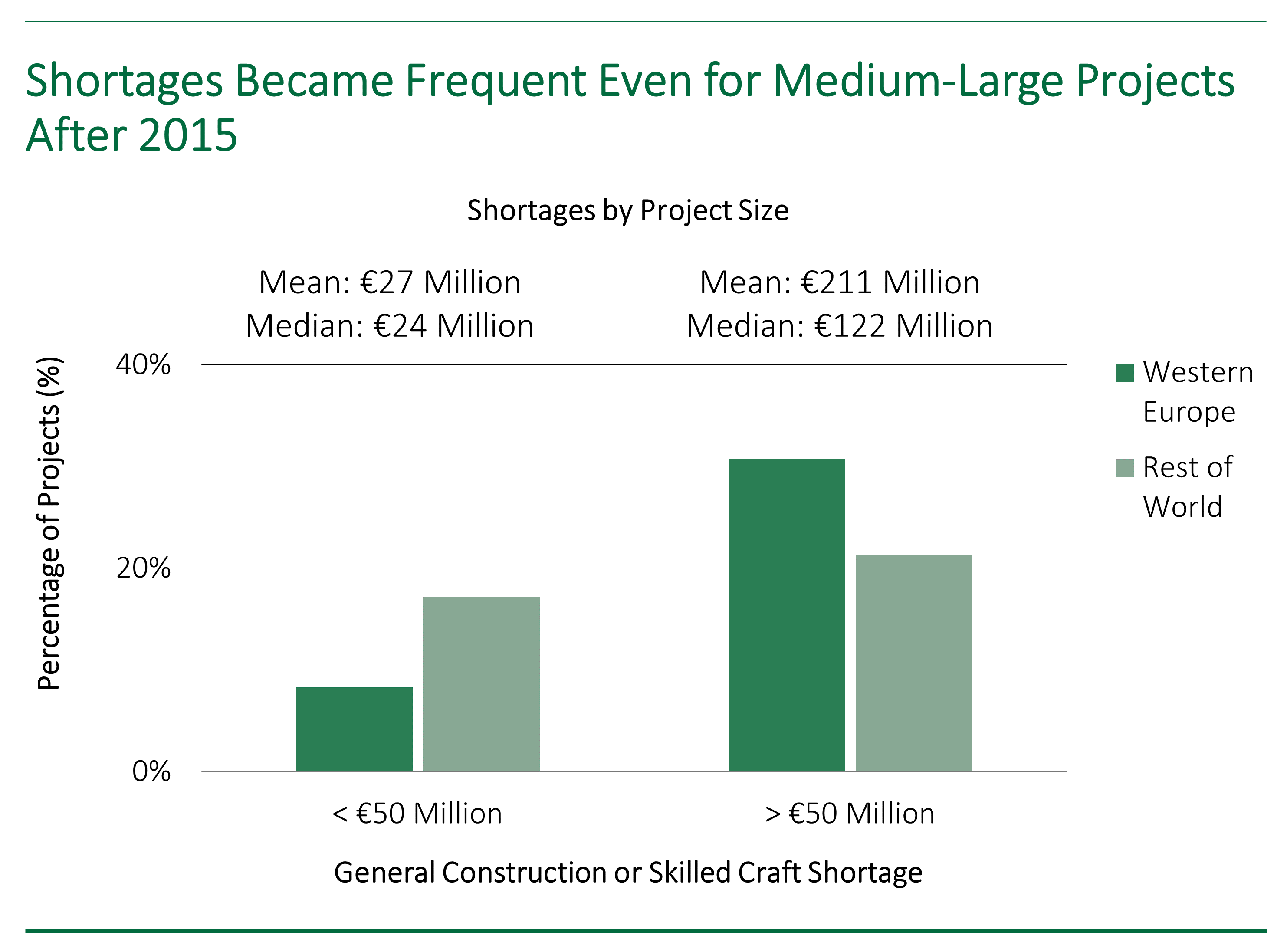

A further breakdown of the data shows that shortages became much more frequent for large projects: After 2015, one in three projects above €50 million reported some kind of construction shortage in Western Europe (Figure 2).

Interestingly, the shortages reported were not limited to the availability of skilled workers. Projects were having difficulty finding bidders and materials, particularly for civil services. For example, project teams reported that due to other regional projects, cement had become more difficult to source.

Project Team Insights

To gain a better understanding of the construction shortage predicament, IPA surveyed a set of Western European project teams to find out if they were anticipating, or currently experiencing, shortages for planned or ongoing projects. The objective was to obtain a real-time view of the availability of individual trades, as well as the industry’s awareness of resource constraints and the planning around them.

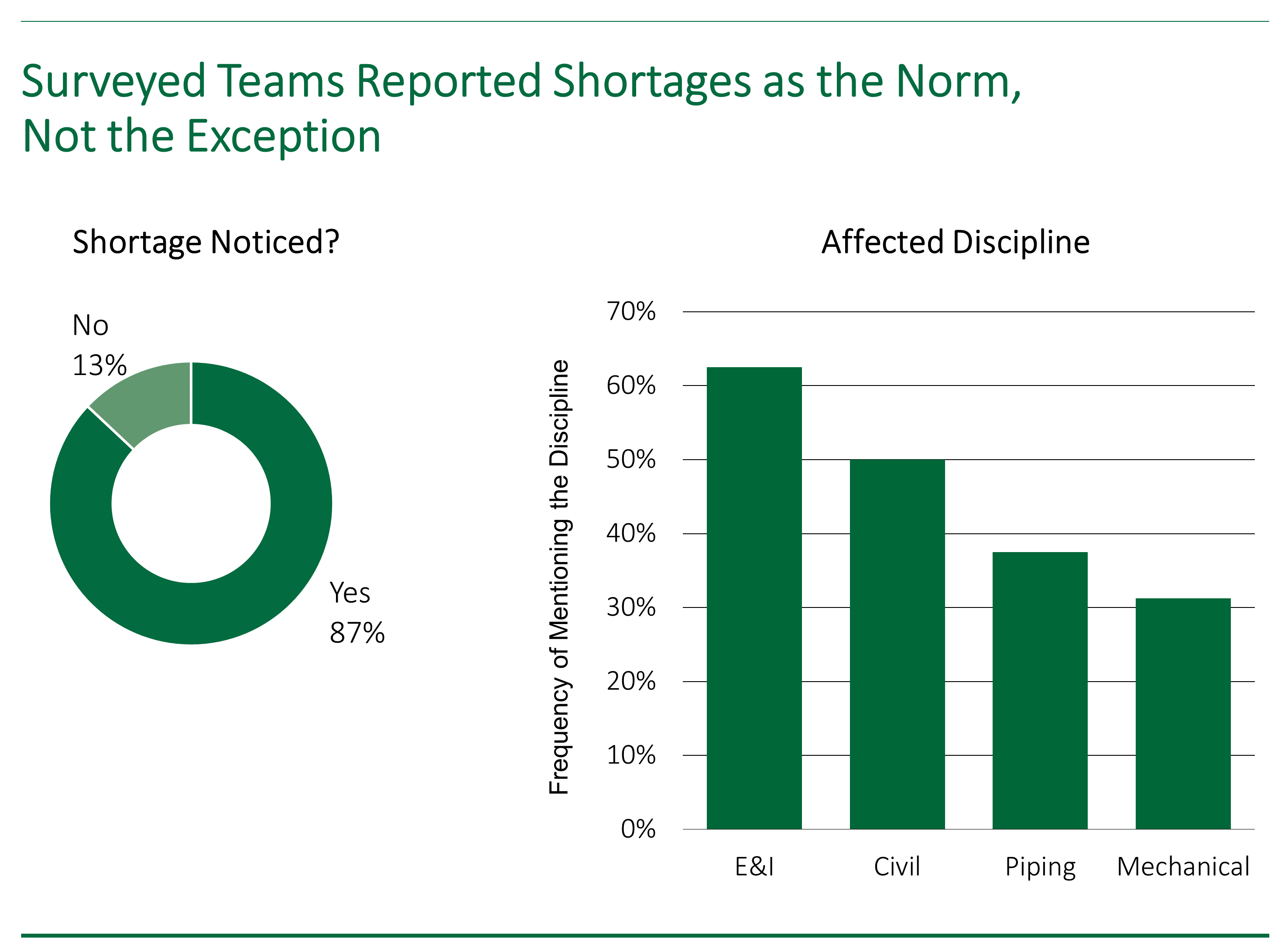

In IPA’s survey, which was executed in early 2020, a few weeks before widespread quarantine regimens and business shutdowns kicked in, close to 90 percent of respondents agreed they had faced—or were facing—shortages in the market (Figure 3).

The disciplines that were most concerning were electrical and instrumentation (E&I) (63 percent) and civil (50 percent). With reporting frequencies of 38 percent and 31 percent, respectively, piping and mechanical were not in ample supply either.

With almost universal concern around the availability of disciplines, we were also interested in knowing how much preparation can mitigate the shortages, in terms of understanding where constraints exist and in planning around those constraints. This preparation could be judged using IPA’s measures of project drivers.

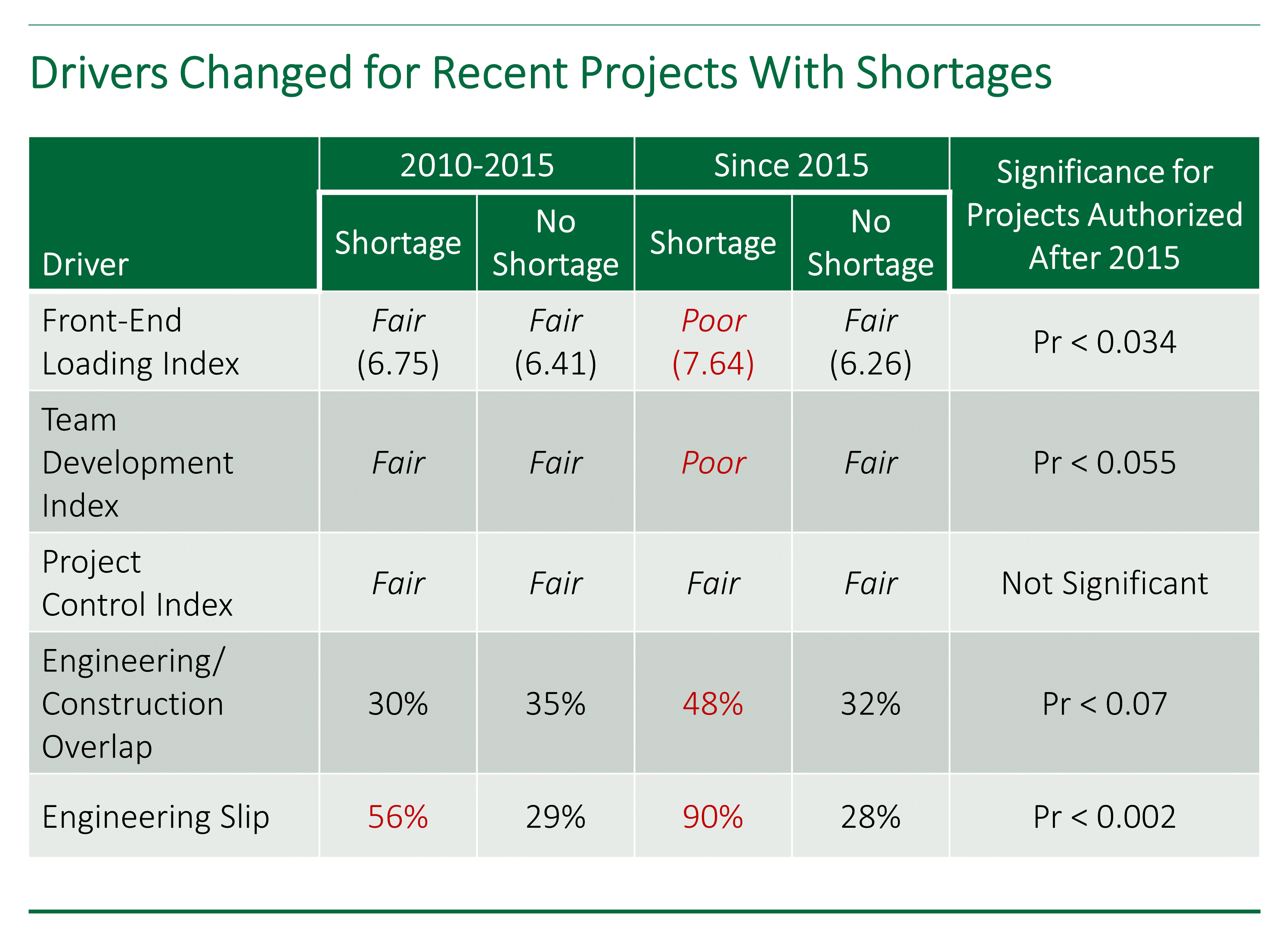

The first and second halves of the decade have not seen significant differences in project drivers overall; however, as shown in Figure 4, the practices of projects that reported shortages recently have worsened significantly. Projects executed after 2015 that reported shortages were rated one category worse in team development (Poor instead of Fair). The Front-End Loading (FEL) Index – which measures among other factors whether labor availability was analyzed — also degraded from Fair to Poor—close to the lowest category of Inadequate—for projects that faced shortages. The results indicate that, not only did the shortages likely come as a surprise to these projects, but also the projects were authorized without the solid foundations necessary to manage and mitigate issues when the shortages occurred. As a further indication of lack of planning, the projects that were affected by shortages experienced massive engineering schedule slip, which almost certainly increased the engineering/construction overlap, resulting in field inefficiencies and a reduced satisfaction with construction workers.[1]

What’s Next?

In the 5 years leading up to 2020, the construction market in Western Europe was arguably heated. The data discussed above show that capital projects, particularly ones valued €50 million or more, frequently reported shortages, with E&I and civil construction being most affected. Most of these projects, however, entered into execution despite planning gaps, resulting in significantly higher cost than estimated.

The COVID-19 virus has thrown the projects and construction markets, like most other things, into various degrees of disarray. In the wake of the pandemic, pressure on the construction industry will vary based on some of the following factors:

- Lower number of projects moving into construction, easing pressure on the construction market

- Reduced access to construction workers due to travel restrictions and more competition from other markets like the Middle East

- New safety protocols (e.g., distancing rules mean lower worker density but potentially worse productivity due to the need for additional training and face masks) increase the pressure on the construction industry

[1] Construction worker satisfaction data not shown.