Sustainability Insights from the Field of Complex Capital Projects

Why do many leaders talk about the importance of sustainability? Can a real competitive advantage be gained when sustainability practices are part of a complex project delivery process? Rather than focusing on the pitfalls of ignoring sustainability initiatives, this article provides insights about how a sustainability strategy can be integrated into complex project development and execution plans to drive superior capital project performance while truly contributing to sustainable development.

What Have We Learned From Successful Complex Capital Projects?

A key success factor for complex projects is the integration of the business opportunity shaping and the Front-End Loading (FEL) processes of the project delivery system.1 An often overlooked reason why complex capital projects fall short of business expectations is the failure on the part of project owners to implement a business-led sustainability strategy that incorporates a shared value creation mentality;2 the implementation of sustainability practices at the right time provides reliable information to strengthen the decision making process during the project development. When this is accomplished, an organization can transform project complexity and risks into a comparative advantage.

Sustainability Practices Strengthen Project Planning

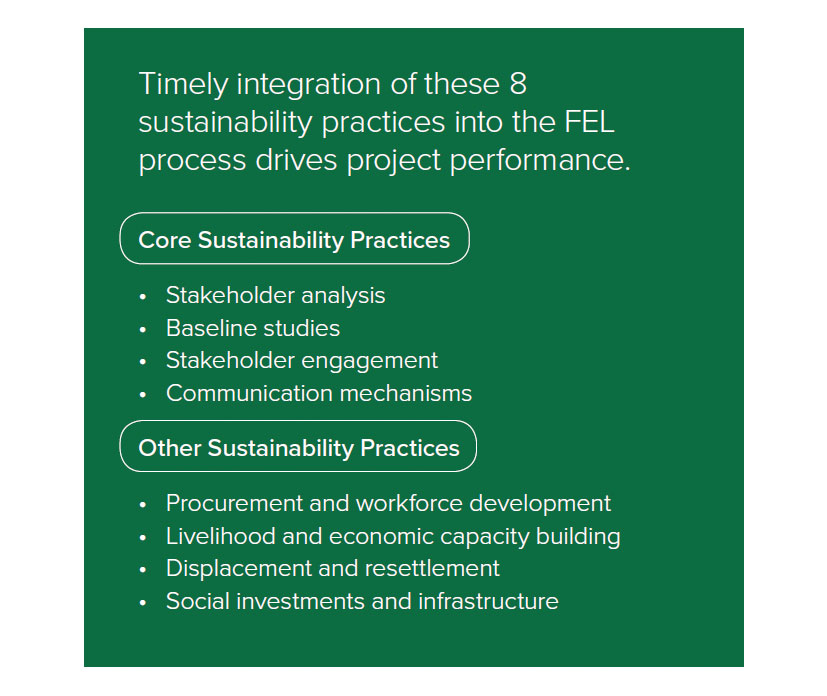

A project’s definition, a key driver of capital project performance measured by IPA’s FEL Index, improves as more sustainability practices are used. An IPA research study that focused on eight sustainability practices employed on more than 170 complex global capital projects reveals that top company performers use more sustainability practices than industry average during the project development phases.

The first four practices—stakeholder analysis, baseline studies, stakeholder engagement, and communication mechanisms—are core practices that are applicable to any industry sector, location, or project size and cost. These practices allow the project team to develop a detailed understanding of the local players, resources, and political environment during the initial project development stages.

Stakeholder mapping, for instance, can show interdependencies among stakeholders and illustrate how the project can influence changes as it progresses (e.g., government regulatory or policy changes, incentives, infrastructure). The aim is to achieve a stable collaboration that enhances the overall value for the sponsoring company and the project stakeholders. External stakeholders—such as governments, local communities, landowners, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), finance banks, and environmental or regulatory entities—are in many cases “difficult to control” because their missions and objectives are often at odds with the project’s expected value. For example, government policies that defend the country’s industrial development, set high taxes on importation of equipment and materials, or have onerous local labor content requirements can delay the start of construction.

Stakeholder collaboration requires transparency and alignment to make shared value decisions; it is usually accomplished by frequent communication and dialog among all stakeholders to build trust, establish a common agenda and measurement system, and set realistic expectations. The next four sustainability practices—procurement and workforce development, livelihood and economic capacity building, displacement and resettlement, and social investments and infrastructure—are non-core practices. Depending on the scope of the project, the effect of their use can range from not economically feasible to providing a major supply chain advantage. These additional practices require an increased level of stakeholder engagement and should be used selectively based on cost-benefit-risk analysis.

High-performing companies dedicated to driving improved capital project performance take supply chain practices seriously.3 From the corporate or business unit level down to project teams, attention should be paid to the integration of supply chain management strategies that include these non-core sustainability practices early in the FEL process. The focus here should be on assessing how sustainable development initiatives can drive competitive advantage, which is especially the case with phased investments in frontier regions designed to work within the local context.

Understanding the needs of communities and fostering a productive dialog not only reduces uncertainty and risk but also reveals opportunities in areas such as water management, hazardous material management, waste management, air quality, biodiversity, land acquisition and resettlement, human rights, energy and climate change, and local employment.4 The opportunity is to achieve synergies, especially in mutually beneficial investments such as shared local infrastructure, training of local workers, and operations logistics support.

Timely Implementation of Sustainability Strategy Drives Project Stability

Complex capital projects are often managed in the context of severe constraints, such as inadequate infrastructure, logistical limitations, and severe climates. Political instability, regulatory issues, and corruption are potential issues that can arise in countries with weak rule of law and lack of transparency.5 Such projects require practices that are implemented at the right time with a structured process. The strategy needs to be planned, documented, and monitored through the project life cycle;6 timing is very important because closure of stakeholder agreements facilitates stability of the project’s scope, cost, and schedule during its execution. Unfortunately, we find many examples of projects that encounter major roadblocks during execution due to valid stakeholder claims after significant investments are deployed; this is a lose-lose situation that can be avoided.

Project Sponsor and Engineering Function Work Together to Implement the Sustainability Strategy

Effective leadership from the project sponsor is essential.7 Early assignment of sustainability experts (e.g., environmental or

social and community experts) is a Best Practice to implement sustainability practices at the right time, but it is not enough to understand the project context and complexity and to implement a sustainability strategy. The project sponsor’s influence is essential and can be particularly difficult in organizations that are more likely to foster a non-cooperating mentality, operate with weak matrices, or have strong functional cultures,8 especially if there are potential conflicts due to incentives that are at odds with cross-functional project requirements.

The project sponsor can work side-by-side with the engineering function to improve the effectiveness of the sustainability strategy. The engineering function can rapidly define the scope and develop cost and schedule estimates (e.g., sustainability investments) in collaboration with external stakeholders to avoid scope creep or roadblock issues during execution. Engineering might also work to improve the productivity of operations and livelihood of nearby communities. For example, water purification capacity can be

added to ensure the health of construction workers and future operators and reduce local population illness. Synergies are the key to mutually beneficial solutions such as increasing the substation capacity to provide electricity to the closest town where a maintenance shop can be established, widening roads to facilitate transportation of produce from neighboring communities, and providing shorter routes for process equipment and materials.

How Does Investment in Sustainability Offer a Path to Competitive Advantage?

An effective sustainability strategy will not only help owner companies acquire the “social license” to operate and reduce risks (e.g., delayed or shelved projects, construction delays, cost growth). An effective sustainability strategy will also improve capital project performance. IPA research into sustainability practices reveals the benefits: capital cost improvement of 10 percent and project schedules that experience fewer delays and are 5 percent faster than industry average. Data show these strategies contribute to a sustainable supply chain advantage.

Lowering Capital Costs Through Sustainability Efforts

Despite higher than average owner’s indirect costs, complex projects that have optimal investment in indirect costs, including sustainability, achieve lower overall capital costs, and achieve more predictable cost and schedules than industry average.9 Previous IPA research of 112 complex global mining, minerals, and metals (MMM) projects revealed that key factors that influence owner’s indirect and engineering costs include whether the project is the first for a company in the country (i.e., first or second generation

projects), experiences community issues (e.g., relocation, compensation, regional content), or has existing infrastructure (e.g., housing, hospitals, roads).

Lowering Capital Costs Through Investment in Sustainability Requires a Share Value Focus

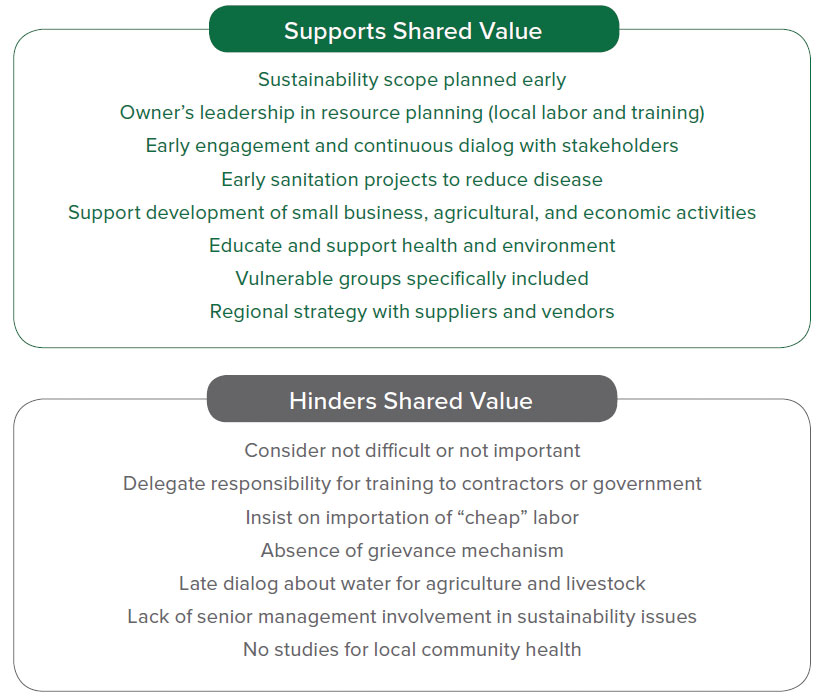

Shared value must be earned through investing time and presence during project development; this is not the first time we see similar requirements—upfront planning and owner presence affect construction safety too. In addition, project’s solar and wind energy, and other capital investments (e.g., green investments) that contribute with climate change initiatives and environmental conservation can be used to establish mutually beneficial synergies with local communities.

Investments in sustainability cannot be justified as compliance requirements, risk avoidance, philanthropy, or good corporate citizenship alone; they must be an integral part of the business case and treated as strategic investment with clear profit goals. Business leadership is essential to ensure management integration and early deployment of organizational capabilities necessary to support governance and a sustainability strategy. Adding value to social progress can provide shared prosperity and competitive advantage.10

ENDNOTES

- Edward Merrow, Industrial Megaprojects: Concepts, Strategies, and Practices for Success, J. Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2011.

- Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer, “Creating Share Value,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 2011.

- Thomas Mead, Research Study: Supply Chain Management Practices, IPA, February 2019.

- Félix Parodi, Lessons Learned From Megaprojects, Mining, and Related Infrastructure, 100 Años de la Pontificia, Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima Perú, August 2017. Félix J. Parodi, “Megaprojects Require a Sustainability Strategy That Works: How Much Sustainability Is Good Business?” IPA Western Canada Capital Projects Journal, Volume 4, Issue 1, May 2016. Félix Parodi, Lessons Learned From Megaprojects, Mining, and Related Infrastructure Workshop, Society for Mining Metallurgic, and Exploration SME’s 4th Current Trends in Mining Finance Conference, New York, April 2016.

- Giorgio Locatelli, Giacomo Mariani, Tristano Sainati, and Marco Greco, “Corruption in Public Projects and Megaprojects: There is an Elephant in the Room!” International Journal of Project Management, 35 (2017), pp. 252-268. www.transparency.com

- Lara Keefer and Josh McClellan, Effect of Social Performance Use on Project Outcomes, IPA, March 2017. Lara Keefer, Understanding and Using Sustainability Practices in the Extractive Industries, IPA, August 2016. Kim Kohn and Justyna Kaczmarczyk, Sustainability Practices in the Process and E&P Industries, IPA, December 2015. Lara Keefer, Sustainability and Projects: Looking at Sustainability Through a Project Perspective, IPA, December 2015. Fred Biery and Paul Stanchfield, How Sustainability Practices Influence Project Outcomes & Manage Risks, World Bank/IFCs 7th Annual Sustainability Exchange, Building Sustainability Data Management Systems, June 2013.

- Edward W. Merrow and Neeraj Nandurdikar, Leading Complex Projects: A Data-Driven Approach to Mastering the Human Side of Project Management, 2018 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Gatekeeping for Capital Governance, The IPA Institute, IPA 2018. Paul Barshop, Capital Projects, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2016. Paul Barshop, “Defending the FEL 1 Gate,” Independent Project Analysis Newsletter, Volume 6, Issue 4, December 2014.

- Edgar H. Schein, “Three Cultures of Management: The Key to Organizational Learning,” Sloan Management Review, Fall 1996.

- Jose Miguel Bolivar, MMM Project Owner’s Cost Study, IPA, February 2019.

- Michael E. Porter, Social Progress: The Next Development Agenda, The World Bank, October 29, 2015.