Wanted: A New Type of Business Leader to Fix E&P Asset Developments

The world of exploration & production (E&P) asset developments is seriously challenged even with oil prices higher than USD 100/bbl (at the time of this writing). Over the past decade and a half, the average E&P asset development has delivered only 60% of the value promised at sanction. The remaining 40% of expected value is eroded during asset development and execution. In any other industry, commodity chemicals, grocery stores, you name it, the level of capital discipline demonstrated by E&P businesses could put their firms in jeopardy. And yet the rising tide that lifts all boats—high oil prices and oil company profits—hides and perpetuates poor project performance.

Here is our situation: Our larger and more complex projects over the past nearly 15 years have had generally dismal outcomes. Now, due to the demographics of the industry—both ours and our supply chain providers in the engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) industry—we find ourselves unable to make consistent and robust profits on new field developments even with prices that are by historical standards very good. We need to be realistic and face the problem that things are not going well in our major capital deployments, and history suggests that our decisions have not been good. If nothing changes, there is every reason to believe that things will get much worse before they get better.

The circumstances and contributors to this asset development quagmire is a mess of our doing. There is no use pinning the blame on project management or EPC contractors or the quality of supply chain. That only carries us to despair because supply chain providers also face problems of their own when dealing with owners. We continue to make the same mistakes over and over and over. We do not rigorously follow our own work processes and always make exceptions for “strategic” projects. We have substituted short-term gain for long-term value. But most damaging of all, we chase volumes in the wrong way, and in the process, destroy the most critical drivers of value: production attainment, and reserves recovery. These are the symptoms of the problem, but they are not the source. The source lies at the disconnect between business expectations of project performance and the realities of what is possible today.

Project teams can deliver great projects, and our firm has seen some exceptional teams deliver exceptional projects. The problem is the conflict between business desires and what is realistically possible. Project management and functional leads are responsible for delivering on the business objectives handed to them. The onus, therefore, is on business managers—that is right, the business side of the organizations—to change their mind-set about how to pursue the right projects the right way in today’s environment by tailoring our project development systems.

Broken Promises Gone Unrecognized

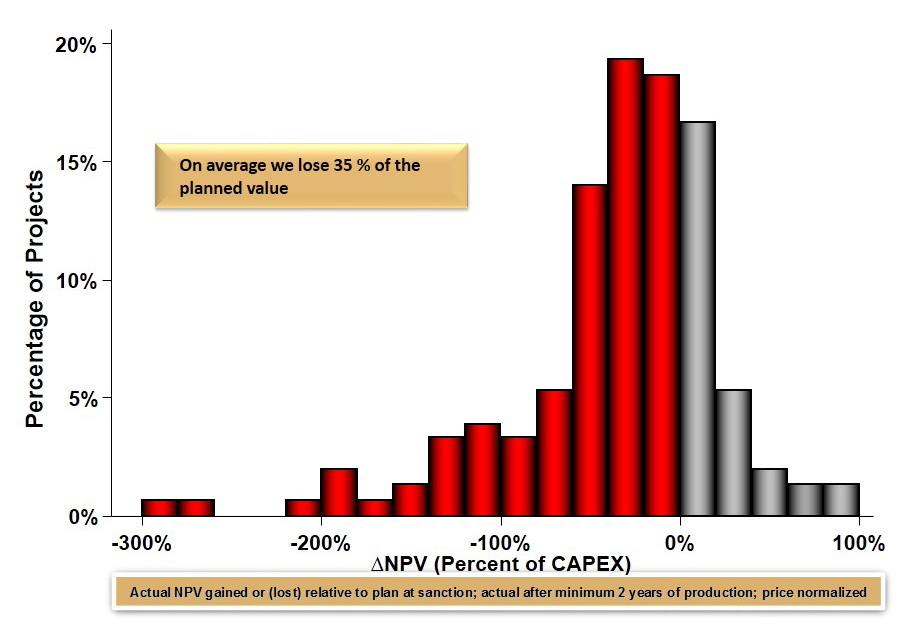

But first, business should understand just how much project value is eroded. So let us step back and look at our performance on projects completed over the past 15 years. Of all the developments completed, 70% of the developments eroded value. On a price normalized basis, these projects delivered less value 2 years after startup compared with the value promised at sanction (Fig. 1).

There are three ways that assets erode value in order of importance: (1) producible reserves are misestimated, (2) growth in capital costs, and (3) inability to deliver the promised schedules for the project.

Of all the projects completed in the past decade, a look back at actual recoverable reserves updated 2 years after startup indicated that actual P50 recoverable reserves fell outside the P10 to P90 range 40% of the time—twice the rate expected, and the bias tends to be negative. In other words, we overestimate our recoverable reserves. This statistic has several profound implications.

First and foremost, it passes judgment on the state of the art for estimating recoverable ranges. Second, it highlights our inability to learn from our past. But, more importantly, given that our ranges were routinely optimistic, it also means that any decision based on those inputs was also too optimistic, which brings into question our decision quality. A company-by-company root cause analysis highlighted several root causes for this performance—some organizational and some technical. However, the most common one was basing scoping decisions on incomplete basic reservoir data. Poor scoping or wrong scope also leads to poor production performance. Production in the second 6 months of startup and all the way up to the fourth year after startup averaged only 78% of the plan. In other words, for every 100 bbl promised, our projects only delivered 78 bbl. Imagine any other situation in which such an operability performance would be acceptable. Yet, we accept this in oil and gas!

The sad part of this is that most businesses do not even recognize the value erosion because the oil price realized is more than assumed at sanction, and it therefore appears that our financial results are better than expected. But what if we structure our project development systems to routinely deliver assets that produce 90 to 95 bbl for every 100 bbl promised, how much better would our financial performance be? Our work with some operators suggests that it is possible with strong business support. So why are we willing to leave so much money on the table?

Growth in Capital Costs

The second way in which assets erode value is growth in capital cost compared with sanction budgets. On average, projects overrun their sanction budgets by an average of 20% in real terms; the actual overruns in nominal terms are much larger. There are several reasons for the increased costs. Although the emergence of new technologies has helped in overcoming various problems, projects continue to be more challenging. Large field developments—at sea and on land—are confined to more difficult places, making access to resources more difficult and expensive. Plus, project input markets are “imperfect” as contractors are struggling to perform and wages are rising at the same time. All the while, productivity is declining, meaning a greater number of expensive labor hours are being incurred.

Significant supply chain breakdowns from equipment, pipe, and pumping vendors to fabrication yards and field services, and to installation, heavy lift, and drilling service providers are partly to blame for this cost growth. For large projects, the supply chain has too many weak links and the number of markets are oligopolistic. Some markets are in perilous condition because of the mismatch of local content requirements with local content availability. Meanwhile, the performance of major engineering firms has been called into question by many in the industry who blame inexperienced and overextended teams, high error rates, and poor project management for higher than expected costs.

So, can anything be done about it? While it is probably difficult to change these systemic issues in the short term, operators can at least recognize the constraints and set reasonable targets for cost and schedule that the supply chain providers have a reasonable shot at delivering.

Speed Over Value

The third way in which assets erode value has a lot to do with the inability to deliver the promised schedules for the project. As mentioned, businesses are setting their projects up for failure by chasing target first oil dates in hopes of making the most from relatively sustained high oil prices. Unfortunately, companies are convinced that they know how to deliver a project fast. The truth is they do not (except for a select few operators), but they keep trying to go fast and end up with slow and expensive projects that do not work.

Of the projects that were completed in the past decade, 60% were schedule-driven. Project cost, estimated production, and even recoverable reserves objectives rank behind. The preference for fast schedules is not surprising. By design, net present value (NPV), the most often used economic metric for projects, places a higher value on early production. As a result, businesses are driven to fast first oil. However, fast schedules come with unrecognized trade-offs, with the biggest and most damaging tradeoff being production shortfall. This also points to a problem with incentive systems in the E&P sector that reward short term performance over long-term measures and as a result, we continue to see poor production and reserves estimates. I suppose there is a silver lining to this dark cloud in that maybe the world is not running out of oil and gas, because we have not produced what we set out to in the first place.

To be clear, no one is advocating that slow projects perform better or preserve value. It would be the wrong conclusion. What is being suggested is that there is a right way to go fast and a wrong way to go fast. The wrong way, which most companies follow, is to not fully recognize or ignore the tradeoffs associated with skipping certain steps, or skipping some data, or making some assumptions, in an effort to move the project along. While many companies use value of information analysis (VOI) to avoid such pitfalls, the optimism bias discussed earlier implies that in many cases we are still underestimating the tradeoffs. The right way is to organize teams and project development models in a way that enables cross-functional work and cooperation and yet permits rapid and effective flow of information and decision making.

The most common justification given for schedule-driven strategies is to plug the proverbial production hole in a company’s production profile, except that because of the way we run the projects, we never really plug the hole. Instead, we accept (or refuse to look) at production shortcomings and lost value, and we continue to push the next project, which leads to another major problem.

Selection and Shaping of Opportunities

The industry’s habit of moving on to the next project post-haste brings us to another issue that has been basically ignored. Most E&P companies have never seen a petroleum accumulation they did not love. They allow opportunities into the scope development process with virtually no scrutiny and often without much knowledge of basic data or understanding of the project context; in fact, most companies spend more time on engineering without first fully understanding project context issues, which is ultimately what gets most projects off the rails today. This means that we sanction projects that are not truly economic because we do not fully know the impact of project context or moving projects along that eventually get recycled, because of unsurmountable contextual difficulties (stakeholder problems, joint venture misalignment, community issues, etc.)

Operators, therefore, need to focus on shaping their opportunities and practicing disciplined portfolio management. Shaping is a business-led process during which businesses must ask hard questions and assess if an opportunity is truly worth moving along to the concept selection stage and directing resources toward. Contrary to traditional thinking, businesses should be looking for more reasons to deselect an opportunity rather than to select an opportunity, lest a marginal opportunity consumes resources that most companies today do not have to spare.

A recently completed assessment of several E&P operators’ portfolio management processes concluded that many companies are spending money and project team resources on large reservoir projects with severe contextual problems. Rather than abandoning these opportunities or going back to produce and assess additional information to resolve context issues, such projects are being recycled through the project work planning process, thus overburdening project organizations and hampering project execution results.

Needed – A New Type of E&P Business Leadership

I have been suggesting—and the data are painfully clear—that business decision making in asset development and execution has not been very good. But who are these “business people” who are responsible and accountable for delivering reserves and producing barrels as promised? In far too many organizations, that question has no clear answer.

In most E&P companies, there is no single person responsible for and accountable for delivering profitable barrels. No wonder, then, that we often do not display deep functional cooperation within our own companies to get best asset development value; with no single person accountable and no incentive, there is no one who can facilitate deep cross-functional integration. Reservoir engineers blame projects, projects blame wells, wells blame reservoirs, and then we move on to the next development. We have been quick to change on the technical side, but very slow to change on the organizational and people side.

Our organizations need to be built to fit the needs of today’s developments, not vice versa. Integration, interface management, and timely flow of information across functions need to be at the core of how we structure our project delivery systems. Ultimately, our organizations must recognize the problem that E&P asset delivery takes a great deal of cross functional work and cooperation and it is not being delivered!

Success will require new kinds of business leaders who will be accountable and responsible for delivering profitable barrels and not just achieving first oil or gas—that is, value over volume. This business leader will need to have an understanding of all the broad aspects of asset development and will take on the role of “chief integrator” of business and project team functions, of different and diverse personnel skill sets, and of delivering cross-functional deliverables. If business leaders with these skills do not exist now, they will have to be made available through training and development. Additionally, the industry needs more active and engaged business leaders who are willing to face the risks and deal with the stakeholder pushback accompanying a more value-driven approach to asset development over speed to first oil. E&P operators, the service sector, SPE, and academia will all have to play a role in shifting our thinking from just projects, which often means facilities, to asset and delivery of profitable barrels.

Ponder the following question: Would the E&P industry perform better if business and asset leaders were held accountable with rewards tied to production performance 2 to 3 years after startup? The historical record makes the case to at least debate this issue. The reasons against such changes are many: multiple stakeholders are involved, understanding reservoir performance takes time and is an art, we are still making money, so on and so forth. My guess is that the influence of these reasons on our outcomes is much smaller than the root cause, meaning that our project development and execution model is unsuitable for contemporary projects.

The stakes are too high for companies that are unable or unwilling to change. In fact, undisciplined project portfolio management and the cost of delivery are likely to put some companies out of business. Our experience working with a few of the operators who have embraced the new realities suggest that these challenges can be overcome as long as there is strong and the right kind of business support. Of those that remain, only companies with adequately shaped opportunities, lean portfolios, and a project development model designed around the flow of information will be successful. Only the fittest will survive!

Originally published in the October 2014 issue of the Journal of Petroleum Technology. Reprinted on IPAGlobal.com with permission.