Why Does Construction Safety Suffer In Pharmaceutical Projects?

Good project safety is the right thing to do; most owners agree that they have a moral obligation to do whatever possible to reduce construction worker injuries and deaths while they are building their capital assets. In addition, good safety brings about other benefits. A history of good construction safety can enhance a company’s image and reputation, and good project safety translates into good company safety. Good safety can also mean lower insurance costs.

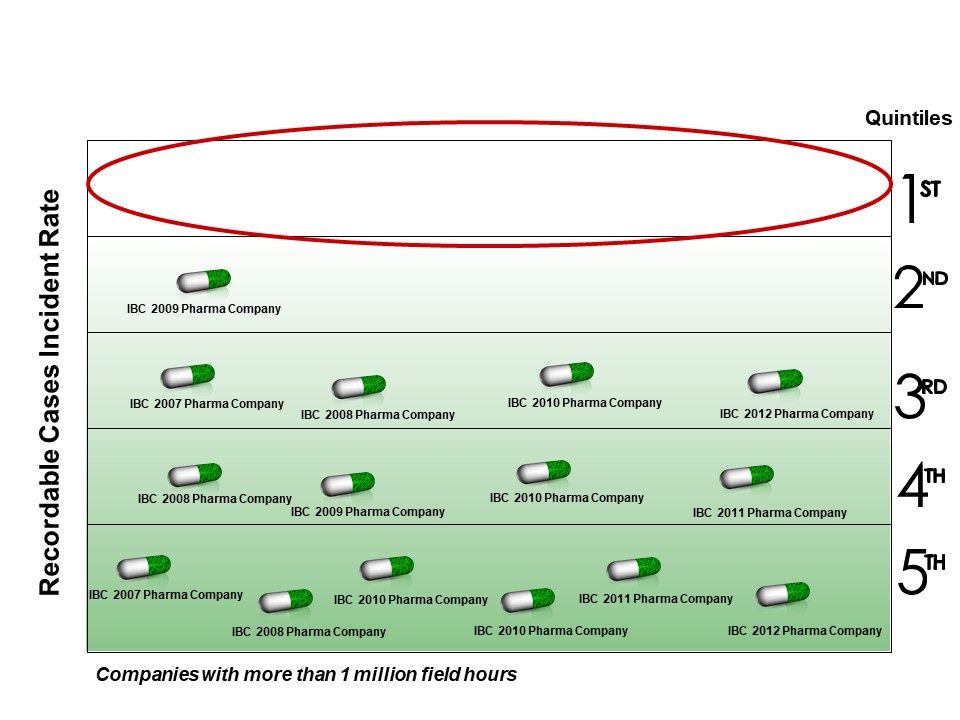

Figure 1

Figure 1

The pharmaceutical industry (pharma) often congratulates itself on its safety; however, IPA research shows that the oil refining, commodity, and specialty chemicals industries all have better safety than pharma. IPA reports on safety by company at its annual Industry Benchmarking Consortium (IBC) meetings, and as seen in Figure 1, over the past 5 years, no pharma company had top quintile performance for total recordable incidents.

We used our database to answer the following questions:

- Why do pharma projects have poorer safety performance than Industry?

- What practices improve the safety performance for pharma projects?

We developed two sets of projects from the IPA Downstream Projects Database: (1) a set of 238 pharma projects that were recently completed by 15 pharma and biotech companies and (2) a set of 2,789 refining and chemicals projects (Industry) that were recently completed by 74 companies; all projects had more than 10,000 field hours. The two sets are similar in project size (cost) and project types. The objective was to limit the sample to recent projects with enough worker exposure hours to ensure variability. We also eliminated projects from the Middle East and Asia; IPA data show that safety statistics on incidents from these regions are so extraordinarily low that the only explanation is underreporting.

We first checked to see if project characteristics—process type, project type, size, and contracting and target setting approaches—might explain the safety differences. We found that civil projects have a worse safety record; however, the trend is across all industries and does not explain differences in performance between pharma and chemical and refining projects. We also disproved a popular hypothesis that aggressive cost or schedule targets increase safety risks, as we found no correlation between target setting and ultimate safety performance.

Project Practices Drive Safety Outcomes

IPA’s analysis then concluded that project practices rather than project characteristics drive outcomes. Our analysis confirmed that every Best Practice benchmarked by IPA shows a significant correlation with recordable incident frequency. The results hold even after we control for project characteristics to eliminate any potential bias.

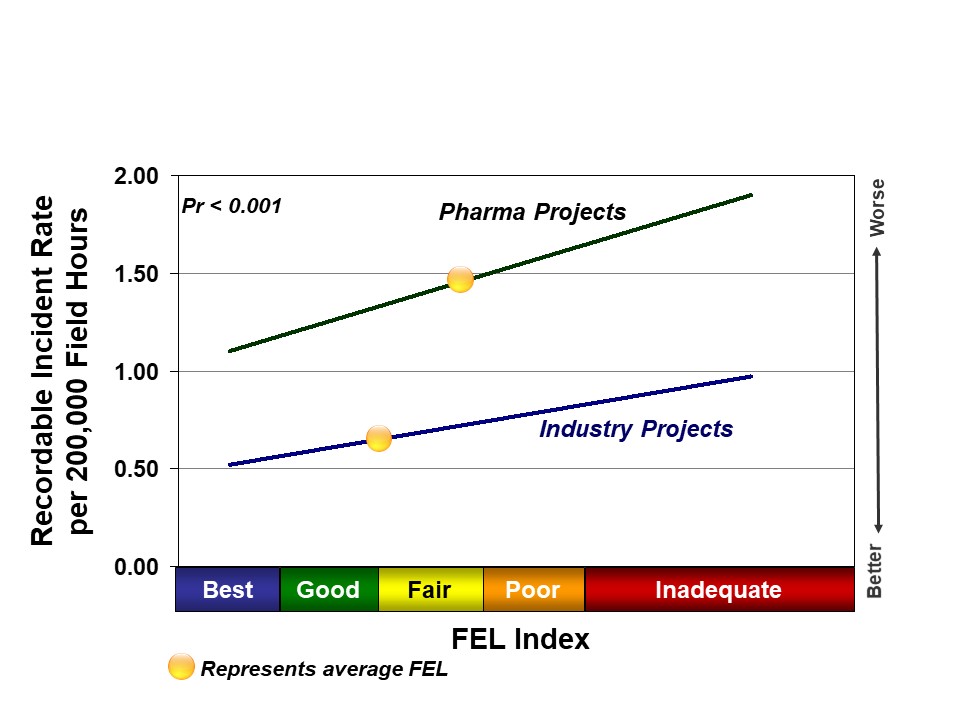

Project definition, or level of Front-End Loading (FEL), at authorization is a key driver of safety outcomes. We hypothesize that better planning leads to more organized projects and fewer changes in the field, which leaves fewer opportunities for accidents. Projects that proceed into execution with Inadequate project definition have significantly higher incident rates than those with Best Practical definition. This relationship is true for all industries. Recent pharma projects, on average, achieved Fair to Poor FEL at authorization; recent Industry projects achieved Good to Fair FEL, on average. The lagging pharma project definition helps explain some of the safety differences between the two groups, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2

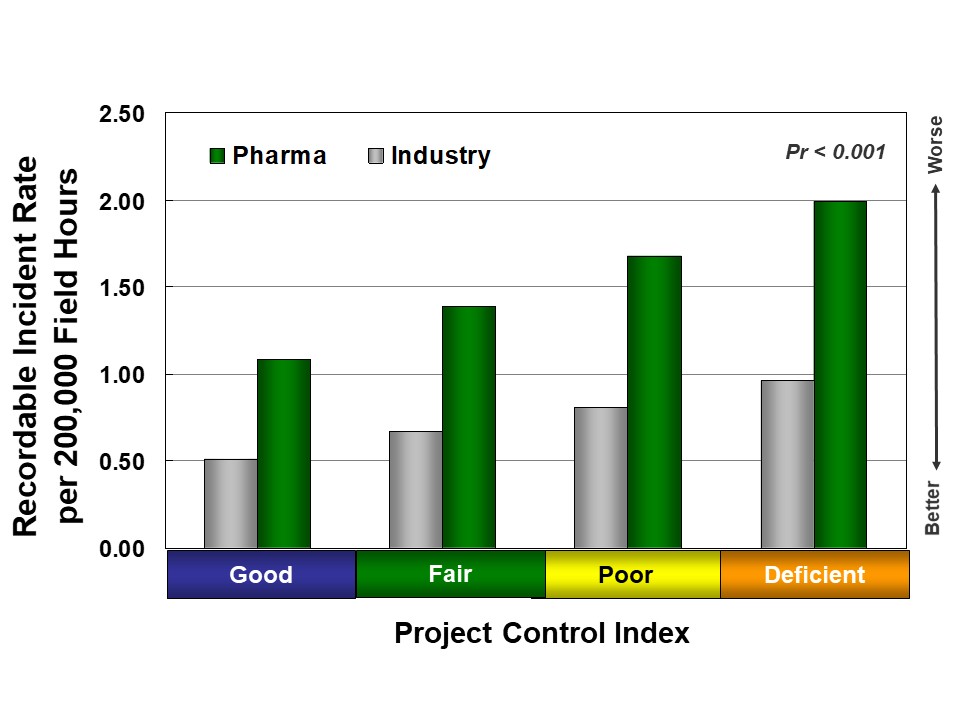

Better execution discipline also leads to better safety for pharma and other industries, as shown in Figure 3. First, project controls, which result in more organized projects, allow owners to identify potential problems early, develop mitigation plans, and better use their more detailed knowledge of field activities. In addition, more active and visible owner involvement helps foster better safety culture.

Figure 3

Inadequate project controls frequently lead to an increase in major late changes. Major late changes disrupt field work and increase the likelihood of accidents; pharma projects are more likely to experience major late design changes than other industry sectors, leading to worse safety. In fact, two-thirds of pharma projects record at least one major change after project authorization, compared to 50 percent of chemical and refining projects.

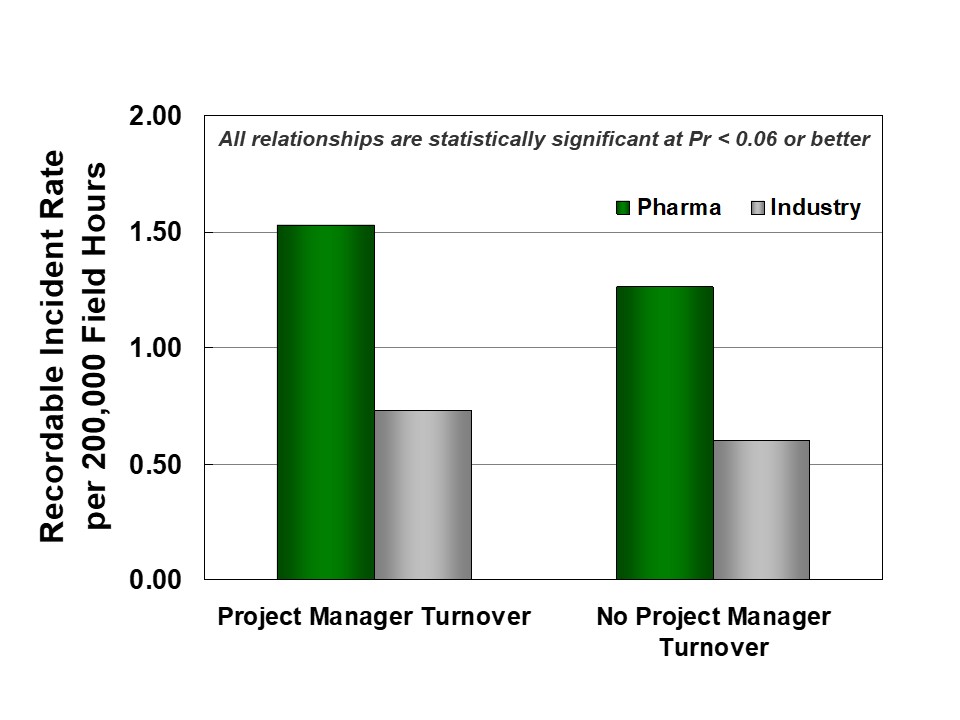

Second, continuity during execution supports better project organization and reduces safety incidents. IPA research shows that project manager turnover tends to destabilize projects and lead to worse safety. As shown in Figure 4, pharma projects are more likely to experience turnover than Industry projects.

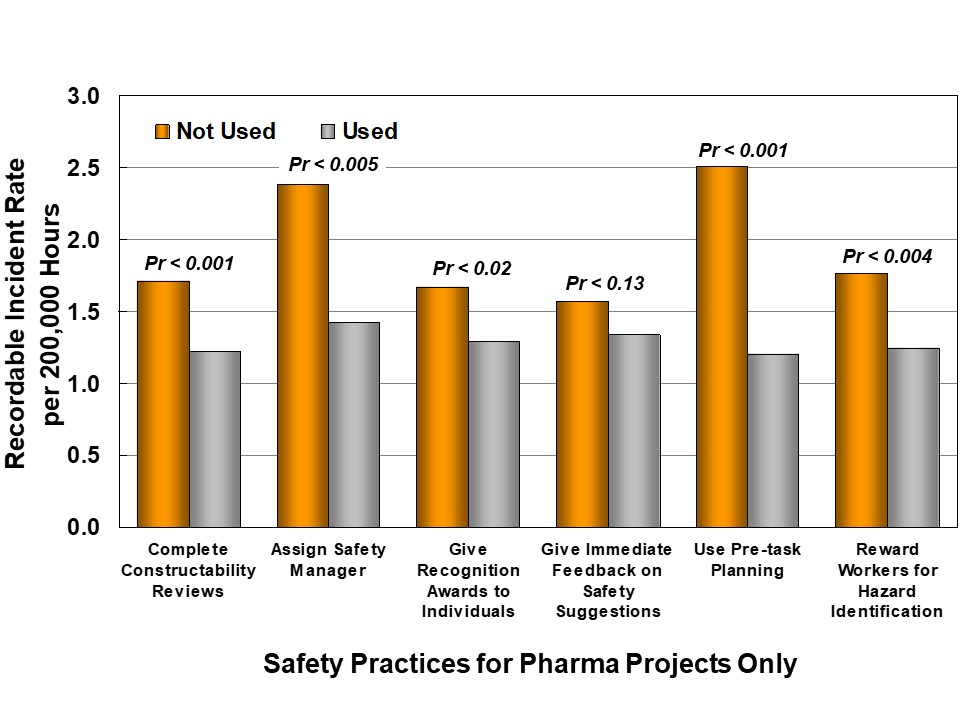

IPA also collects information about project safety practices; in this study, we evaluated each practice to determine if it had a measurable effect on safety, as shown in Figure 5. Some of these practices are so commonly used that it is not possible to test their possible influence. However, there are six safety practices, in addition to project definition and controls, which show statistical correlations with recordable incident frequency:

- Complete Constructability Reviews

- Assign Safety Manager

- Give Recognition Awards to Individuals

- Give Immediate Feedback on Safety Suggestions

- Use Pre-Task Planning

- Reward Workers for Hazard Identification

Pharma projects are less likely than Industry to consistently use these Best Practices. Differences are most striking (and statistically significant) for Constructability Reviews and 3D CAD, immediate feedback on safety suggestions, and pre-task planning.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Good Preparation Leads to Project Safety

In conclusion, the likelihood of poor safety is not random; better prepared projects are in a better position to achieve good safety. There are specific Best Practices that correlate with safety, and these relationships hold across different industry sectors. Pharma projects achieve worse safety than Industry projects in large part because of the inconsistent application of these practices. Therefore, in order to improve project safety performance, it is critical that pharma companies enforce the use of Best Practices on every project.

However, the differences in safety performance between pharma and chemicals and refining are so large that the use of Best Practices alone cannot explain them. Publicly available data from the Occupational Health and Safety Administration in the US show that the overall operational safety statistics for pharma are worse than refining and chemicals. One possible explanation for this gap in safety performance is that, in general, operational conditions in pharma are not as inherently dangerous as in the refining and chemicals industries. Therefore, the strict safety procedures and culture of the refining and chemicals industries translates into all aspects of the industry, including construction safety. In order to close this gap, pharma companies should review their safety cultures and approaches toward safety throughout their organizations. The objective should be to instill a heightened level of safety awareness that becomes a core company value.