THE PROBLEM

A Europe-based global consumer products company approached IPA with a resourcing question. The company assumed they were resourced beyond their need and could reduce their direct costs and accommodate a planned portfolio expansion by shifting some project work to contractors.

After a discussion with senior company leadership, IPA observed internal differences of opinion, with some leaders stating the organization could easily absorb more work, while others thought the organization was ready to break. Further discussions highlighted that projects were taking too long, which was keeping resources mobilized for long periods; that miscommunication often led to re-work, cannibalizing resources; and that some projects needed fixing once completed. These contradictions signaled that opportunities existed to improve how projects are delivered and that the issues required more than a simple fix: a thorough system diagnostic was required to discover the root causes behind the issues.

WHAT IPA DID

The ultimate business value projects generate is only as good as the elements that support the system used to manage projects. These elements are specific to the company’s DNA (its portfolio and investment rules) and include:

- The work process: what system the company has in place to guide project teams to achieve good performance on projects

- The organization: who is available and accountable to drive performance on projects and how they are organized

- The governance rules: how project decisions are made and accountabilities allocated

- Performance management: how the system measures and reports performance

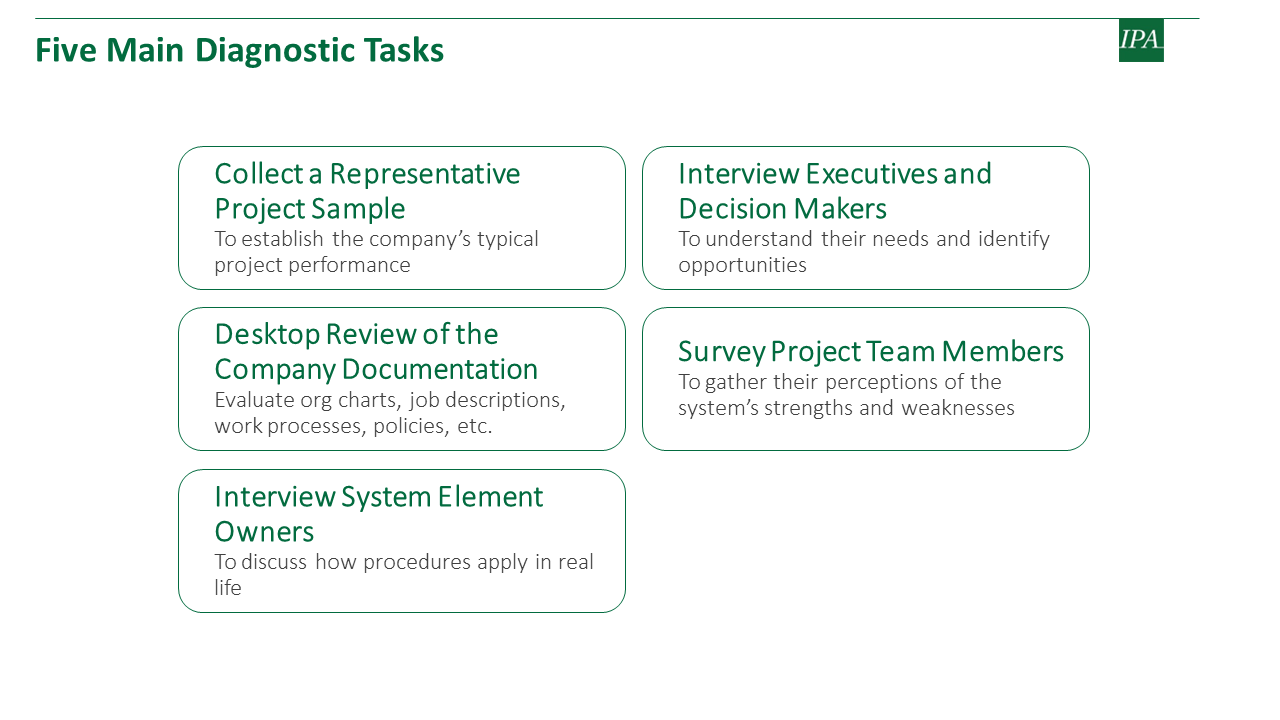

As proposed, the system diagnostic would provide the client with a complete understanding of the improvements required to tackle the expanding portfolio and to deliver it on time. IPA used five main tasks to gather system information:

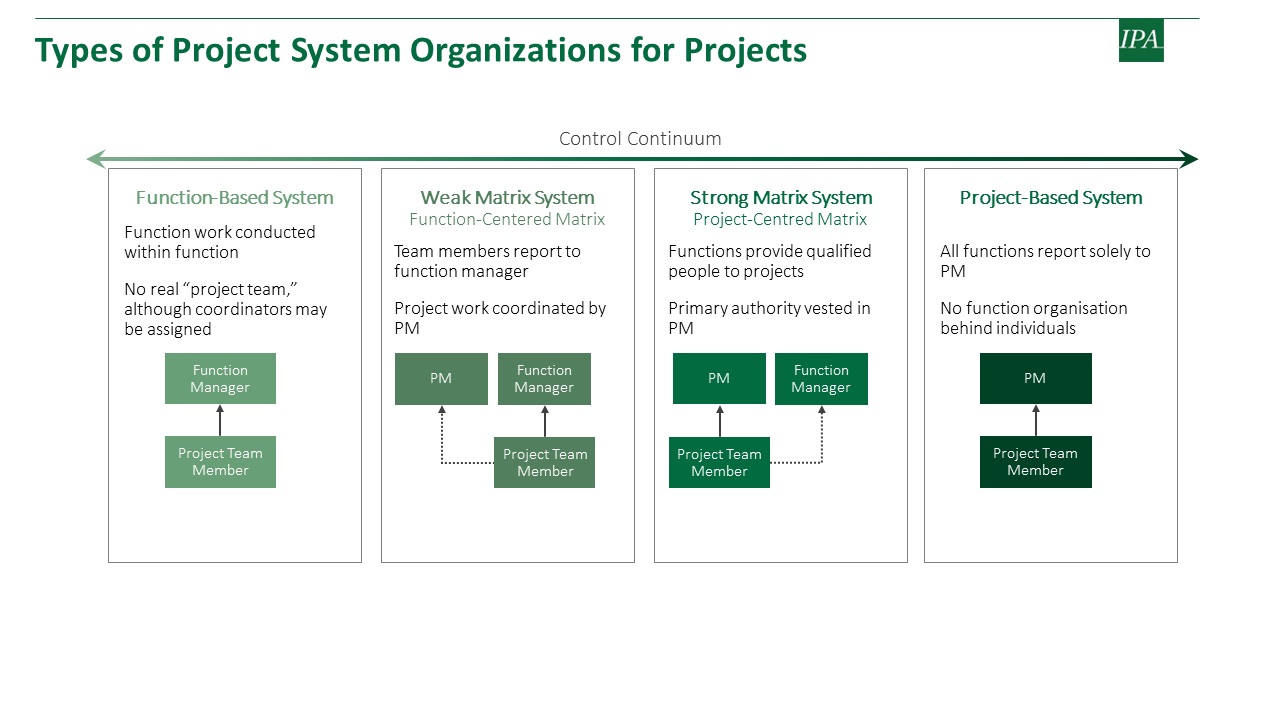

Although our work with this client spanned many areas, for this case study, we focus on the organizational review to address the resourcing question. IPA found that project resources were spread across various independent groups with the work done independently in silos, not accounting for other groups’ risks. In the control continuum shown below, this company’s system most closely resembles a weak matrix organization. The advantages of this approach include strong functional competency and projects being more closely aligned with the business, but this approach also comes with disadvantages.

For the client, this organizational setup translates into the many late changes, as reported in the project sample. Indeed, the project management hubs sit in various parts of the organization: some sit within business areas, while others sit within site-based maintenance groups or within a central project organization dedicated mostly to one large site. This means teams are often led by functions that have no authority over their team members, and team members are not nominatively assigned to projects, but rather support the leader as a functional group, breaking any sense of input continuity and overall accountability.

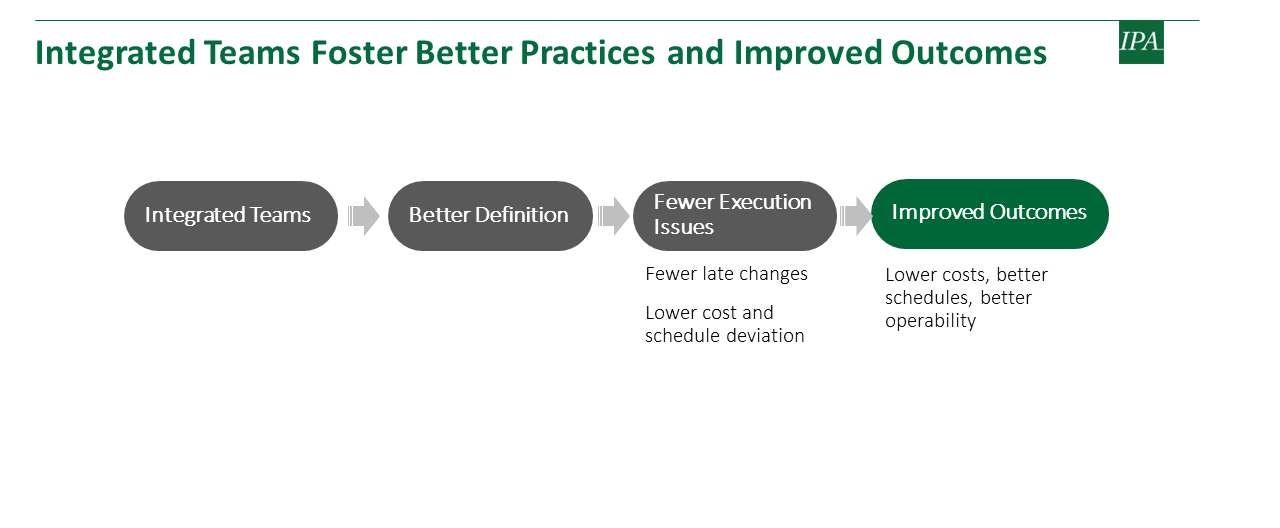

The analysis also revealed that the number of full time equivalents in the current portfolio is adequate but unbalanced, with some essential functions missing. We confirmed that engineering is well represented in the organization, as many believed. However, we also found that engineers take on many roles outside their functional duties—from construction management to estimating and scheduling. Some even serve as operations or maintenance representatives. Moreover, the lack of some essential functions meant that none of the sample projects we looked at had an integrated team, greatly diminishing the project outcomes.

We also found that the central engineering organization was overly occupied with helping manufacturing sites with smaller projects, resulting in fewer dedicated resources being available for large and complex projects. This particular problem had never surfaced to the executives before this analysis because the portfolio never took into account resource availability. Instead, the problem of staffing fell to the project engineering department.

The analysis revealed that the organization was understaffed in key functions and inadequately organized to tackle the planned upcoming growth in new regions.

HOW IT TURNED OUT

IPA’s analysis showed that lack of company resources was not the problem. Rather, the company’s resourcing issue was really a symptom of a deeper problem and required organizational changes. To resolve the system problems identified, IPA suggested a transformation program, which included:

- A set of organizational workstreams to:

- Gradually install a central project management and engineering organization that is responsible for end-to-end delivery of project objectives. This includes restructuring some organizations (including a parallel workstream on staffing up sites to handle their small projects independently).

- Add new competences and re-train some engineers to other key functions.

- Staff up for the upcoming portfolio through a mix of direct hire and bespoke contracting to cope with the regional peaks and valleys of the portfolio.

- A portfolio management workstream to formalize the portfolio management framework and provide a clear long-term view of projects, resource requirements, and resource utilization.